martes, 31 de diciembre de 2013

Huey P. Newton

Lessons from the life of Panther leader Huey P. Newton

1942-1989By Abayomi Azikiwe

Editor, Pan-African News Wire

Published Feb 9, 2012 8:52 PM

Walter Newton was a hardworking southern African American. According to Huey, “During those years in Louisiana he worked in a gravel pit, a carbon plant, in sugar cane mills, and sawmills. This pattern did not change when we moved to Oakland.” (Revolutionary Suicide, 1973)

“As a youngster,” Newton continued, “I well remember my father leaving one job in the afternoon, coming home for a while, then going to the other. In spite of this, he always found time for his family. It was always high-quality time when he was home.”

Newton also mentioned that his father was a Baptist minister in Louisiana and in Oakland, Calif., where the family settled in 1945. Oakland was a center of African-American migration during the 1940s. War production had opened up new jobs for the working class.

Newton became alienated from his teachers and educational administrators in the Oakland public school system. He rebelled as an individual, fighting and defying his instructors.

Newton wrote that in his last year in high school, he was functionally illiterate. However, his older brother, Melvin, helped him develop an interest in reading. He studied Plato and Aristotle, became a ferocious reader, and took up sociology and law in Oakland City College.

Nonetheless, Newton became involved in petty hustling to raise money and so he could have leisure time to read books and enjoy time free from work. Eventually he landed in Alameda County Jail in 1964. In 1965 when he got out of jail, he began to hang out with Bobby Seale, whom he had met earlier.

Becoming disenchanted with existing groups they were active in, the two aimed at forming an organization that would rely on the most oppressed segments in the African-American community. Newton wrote, “None of the groups were able to recruit and involve the very people they professed to represent — the poor people in the community who never went to college, probably were not even able to finish high school.”

Origins of the Black Panther Party

The concept of the Black Panther Party grew out of the Civil Rights struggles in Lowndes County, Ala., in 1965-66. Founded after the March 1965 Selma to Montgomery march, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization made an attempt to form an independent, Black-led political party in opposition to both Democrats and Republicans.

Local activists started the LCFO in cooperation with organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael and other activists were instrumental in formulating LCFO’s tactics and strategy.

The concept spread, and by 1966 the Alabama Black Panther Party had been established. The organization took up arms in defense of the right of African Americans to organize and to vote. The presence of armed African Americans caught the imagination of youth around the country. Soon Black Panther organizations existed around the United States.

Newton and Seale founded the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland in October 1966. In California by early 1967, at least three different groups were organizing around the Black Panther symbol. By 1968, in a complicated set of historical circumstances that extend beyond the scope of this article, the most well-known and predominant group within the Black Panther movement centered around Newton and Seale.

During this period the prevailing philosophy of nonviolent resistance came under ideological attack within the African-American community. Rebellions erupted in hundreds of cities between 1963 and 1968.

On Oct. 28, 1967, Newton, then Minister of Defense of the Black Panther Party, was involved in a shoot-out with police; one officer was killed and another wounded. Newton was also seriously wounded and spent nearly three years in the California prison system.

Growth & repression of the Panthers

During Newton’s 1967-1970 incarceration, the BPP grew into a national organization, headquartered in Oakland and encompassing some of the most revolutionary men and women. The FBI, under the administrations of both Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard M. Nixon, in collusion with local cops, declared war on the Panthers and other revolutionary African-American organizations. In that war the police, with FBI coordination, killed dozens of BPP members, arrested and framed-up hundreds on fabricated criminal charges, and drove others underground or into exile.

Such pressure from the federal government led to major political splits within the BPP between 1969 and 1971. In 1969, Stokely Carmichael resigned along with many of his supporters. In 1971, there was a split between Newton and Eldridge Cleaver and their respective supporters.

These developments occurred simultaneously with major restructuring of the U.S. labor force. Production facilities that had employed African Americans post-World War II began to relocate outside urban communities to small towns and other states.

Newton’s tragic death in 1989 must be viewed in this context. The leader, who had been hounded for years by Oakland authorities, was killed there on Aug. 22. His death was the result of his involvement with crack-cocaine drug use, which had devastated the African-American community throughout the country during the late 1980s.

Nevertheless, the Black Panther Party’s example remains a high point in the overall struggle against national and class oppression. The Panthers’ impact and their uncompromising challenges to the system of capitalist exploitation influenced other oppressed nations, including Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Asians, Native peoples and radical whites.

Today the need for revolutionary organizations is just as important as, if not more than, it was in the 1960s and 1970s. With the decline in wages and the rise of social misery among the working class and impoverished, it is only through the fundamental transformation of U.S. society that the majority of people inside the country and internationally will be totally liberated.

Articles copyright 1995-2012 Workers World.

Verbatim copying and distribution of this entire article is permitted in

any medium without royalty provided this notice is preserved.

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email: ww@workers.org

Subscribe wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news DONATE

Workers World, 55 W. 17 St., NY, NY 10011

Email: ww@workers.org

Subscribe wwnews-subscribe@workersworld.net

Support independent news DONATE

lunes, 30 de diciembre de 2013

Monsanto

Monsanto, the TPP, and Global Food Dominance

Posted on November 26, 2013 by Ellen Brown

“Control oil and you control nations,” said US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the 1970s. ”Control food and you control the people.”

Global food control has nearly been achieved, by reducing seed diversity with GMO (genetically modified) seeds that are distributed by only a few transnational corporations. But this agenda has been implemented at grave cost to our health; and if the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) passes, control over not just our food but our health, our environment and our financial system will be in the hands of transnational corporations.

Profits Before Populations

According to an Acres USA interview of plant pathologist Don Huber, Professor Emeritus at Purdue University, two modified traits account for practically all of the genetically modified crops grown in the world today. One involves insect resistance. The other, more disturbing modification involves insensitivity to glyphosate-based herbicides (plant-killing chemicals). Often known as Roundup after the best-selling Monsanto product of that name, glyphosate poisons everything in its path except plants genetically modified to resist it.

Glyphosate-based herbicides are now the most commonly used herbicides in the world. Glyphosate is an essential partner to the GMOs that are the principal business of the burgeoning biotech industry. Glyphosate is a “broad-spectrum” herbicide that destroys indiscriminately, not by killing unwanted plants directly but by tying up access to critical nutrients.

Because of the insidious way in which it works, it has been sold as a relatively benign replacement for the devastating earlier dioxin-based herbicides. But a barrage of experimental data has now shown glyphosate and the GMO foods incorporating it to pose serious dangers to health. Compounding the risk is the toxicity of “inert” ingredients used to make glyphosate more potent. Researchers have found, for example, that the surfactant POEA can kill human cells, particularly embryonic, placental and umbilical cord cells. But these risks have been conveniently ignored.

The widespread use of GMO foods and glyphosate herbicides helps explain the anomaly that the US spends over twice as much per capita on healthcare as the average developed country, yet it is rated far down the scale of the world’s healthiest populations. The World Health Organization has ranked the US LAST out of 17 developed nations for overall health.

Sixty to seventy percent of the foods in US supermarkets are now genetically modified. By contrast, in at least 26 other countries—including Switzerland, Australia, Austria, China, India, France, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Greece, Bulgaria, Poland, Italy, Mexico and Russia—GMOs are totally or partially banned; and significant restrictions on GMOs exist in about sixty other countries.

A ban on GMO and glyphosate use might go far toward improving the health of Americans. But the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a global trade agreement for which the Obama Administration has sought Fast Track status, would block that sort of cause-focused approach to the healthcare crisis.

Roundup’s Insidious Effects

Roundup-resistant crops escape being killed by glyphosate, but they do not avoid absorbing it into their tissues. Herbicide-tolerant crops have substantially higher levels of herbicide residues than other crops. In fact, many countries have had to increase their legally allowable levels—by up to 50 times—in order to accommodate the introduction of GM crops. In the European Union, residues in foods are set to rise 100-150 times if a new proposal by Monsanto is approved. Meanwhile, herbicide-tolerant “super-weeds” have adapted to the chemical, requiring even more toxic doses and new toxic chemicals to kill the plant.

Human enzymes are affected by glyphosate just as plant enzymes are: the chemical blocks the uptake of manganese and other essential minerals. Without those minerals, we cannot properly metabolize our food. That helps explain the rampant epidemic of obesity in the United States. People eat and eat in an attempt to acquire the nutrients that are simply not available in their food.

According to researchers Samsell and Seneff in Biosemiotic Entropy: Disorder, Disease, and Mortality (April 2013):

Glyphosate’s inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes is an overlooked component of its toxicity to mammals. CYP enzymes play crucial roles in biology . . . . Negative impact on the body is insidious and manifests slowly over time as inflammation damages cellular systems throughout the body. Consequences are most of the diseases and conditions associated with a Western diet, which include gastrointestinal disorders, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, depression, autism, infertility, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

More than 40 diseases have been linked to glyphosate use, and more keep appearing. In September 2013, the National University of Rio Cuarto, Argentina, published research finding that glyphosate enhances the growth of fungi that produce aflatoxin B1, one of the most carcinogenic of substances. A doctor from Chaco, Argentina, told Associated Press, “We’ve gone from a pretty healthy population to one with a high rate of cancer, birth defects and illnesses seldom seen before.” Fungi growths have increased significantly in US corn crops.

Glyphosate has also done serious damage to the environment. According to an October 2012 report by the Institute of Science in Society:

Agribusiness claims that glyphosate and glyphosate-tolerant crops will improve crop yields, increase farmers’ profits and benefit the environment by reducing pesticide use. Exactly the opposite is the case. . . . [T]he evidence indicates that glyphosate herbicides and glyphosate-tolerant crops have had wide-ranging detrimental effects, including glyphosate resistant super weeds, virulent plant (and new livestock) pathogens, reduced crop health and yield, harm to off-target species from insects to amphibians and livestock, as well as reduced soil fertility.

Politics Trumps Science

In light of these adverse findings, why have Washington and the European Commission continued to endorse glyphosate as safe? Critics point to lax regulations, heavy influence from corporate lobbyists, and a political agenda that has more to do with power and control than protecting the health of the people.

In the ground-breaking 2007 book Seeds of Destruction: The Hidden Agenda of Genetic Manipulation, William Engdahl states that global food control and depopulation became US strategic policy under Rockefeller protégé Henry Kissinger. Along with oil geopolitics, they were to be the new “solution” to the threats to US global power and continued US access to cheap raw materials from the developing world. In line with that agenda, the government has shown extreme partisanship in favor of the biotech agribusiness industry, opting for a system in which the industry “voluntarily” polices itself. Bio-engineered foods are treated as “natural food additives,” not needing any special testing.

Jeffrey M. Smith, Executive Director of the Institute for Responsible Technology, confirms that US Food and Drug Administration policy allows biotech companies to determine if their own foods are safe. Submission of data is completely voluntary. He concludes:

In the critical arena of food safety research, the biotech industry is without accountability, standards, or peer-review. They’ve got bad science down to a science.

Whether or not depopulation is an intentional part of the agenda, widespread use of GMO and glyphosate is having that result. The endocrine-disrupting properties of glyphosate have been linked to infertility, miscarriage, birth defects and arrested sexual development. In Russian experiments, animals fed GM soy were sterile by the third generation. Vast amounts of farmland soil are also being systematically ruined by the killing of beneficial microorganisms that allow plant roots to uptake soil nutrients.

In Gary Null’s eye-opening documentary Seeds of Death: Unveiling the Lies of GMOs,Dr. Bruce Lipton warns, “We are leading the world into the sixth mass extinction of life on this planet. . . . Human behavior is undermining the web of life.”

The TPP and International Corporate Control

As the devastating conclusions of these and other researchers awaken people globally to the dangers of Roundup and GMO foods, transnational corporations are working feverishly with the Obama administration to fast-track the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a trade agreement that would strip governments of the power to regulate transnational corporate activities. Negotiations have been kept secret from Congress but not from corporate advisors, 600 of whom have been consulted and know the details. According to Barbara Chicherio in Nation of Change:

The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) has the potential to become the biggest regional Free Trade Agreement in history. . . .The chief agricultural negotiator for the US is the former Monsanto lobbyist, Islam Siddique. If ratified the TPP would impose punishing regulations that give multinational corporations unprecedented right to demand taxpayer compensation for policies that corporations deem a barrier to their profits.. . . They are carefully crafting the TPP to insure that citizens of the involved countries have no control over food safety, what they will be eating, where it is grown, the conditions under which food is grown and the use of herbicides and pesticides.

Food safety is only one of many rights and protections liable to fall to this super-weapon of international corporate control. In an April 2013 interview on The Real News Network, Kevin Zeese called the TPP “NAFTA on steroids” and “a global corporate coup.” He warned:

No matter what issue you care about—whether its wages, jobs, protecting the environment . . . this issue is going to adversely affect it . . . .If a country takes a step to try to regulate the financial industry or set up a public bank to represent the public interest, it can be sued . . . .

Return to Nature: Not Too Late

There is a safer, saner, more earth-friendly way to feed nations. While Monsanto and US regulators are forcing GM crops on American families, Russian families are showing what can be done with permaculture methods on simple garden plots. In 2011, 40% of Russia’s food was grown on dachas (cottage gardens or allotments). Dacha gardens produced over 80% of the country’s fruit and berries, over 66% of the vegetables, almost 80% of the potatoes and nearly 50% of the nation’s milk, much of it consumed raw. According to Vladimir Megre, author of the best-selling Ringing Cedars Series:

Essentially, what Russian gardeners do is demonstrate that gardeners can feed the world – and you do not need any GMOs, industrial farms, or any other technological gimmicks to guarantee everybody’s got enough food to eat. Bear in mind that Russia only has 110 days of growing season per year – so in the US, for example, gardeners’ output could be substantially greater. Today, however, the area taken up by lawns in the US is two times greater than that of Russia’s gardens – and it produces nothing but a multi-billion-dollar lawn care industry.

In the US, only about 0.6 percent of the total agricultural area is devoted to organic farming. This area needs to be vastly expanded if we are to avoid “the sixth mass extinction.” But first, we need to urge our representatives to stop Fast Track, vote no on the TPP, and pursue a global phase-out of glyphosate-based herbicides and GMO foods. Our health, our finances and our environment are at stake.

____________________________

Ellen Brown is an attorney, president of the Public Banking Institute, and author of twelve books, including the best-selling Web of Debt. In The Public Bank Solution, her latest book, she explores successful public banking models historically and globally. Her blog articles are at EllenBrown.com.

Meditación

Meditación produce grandes cambios emocionales en el cerebro

26/12/13 Por Arshdeep Sarao

Neurólogos de los Estados Unidos descubrieron recientemente que ocho semanas de meditación en compasión pueden producir cambios cerebrales a largo término y desarrollar rasgos positivos en la personalidad. El equipo encontró que la meditación mejora la estabilidad emocional y la respuesta al estrés alterando la actividad de la amígdala-una región cerebral involucrada en regular las emociones y la atención.

“Este estudio contribuye a un creciente cuerpo cada vez mayor de la evidencia de estudios científicos, que la práctica de la meditación afecta al cuerpo y el cerebro de maneras mensurables”, afirmó la doctora Dr. Gaëlle Desbordes, del Hospital General de Massachusetts, a La Gran Época vía email. Para estudiar los efectos de la meditación, participantes adultos fueron entrenados durante ocho semanas en la meditación compasiva o meditación consciente (para desarrollar la conciencia de la respiración, del pensamiento y las emociones). A un tercer grupo de control se les impartió educación de la salud.

Tres semanas antes y después del entrenamiento, los cerebros de los participantes fueron escaneados mientras observaban una serie de imágenes con distinto contenido emocional.

El grupo de meditación consciente mostró una reducción en la activación de la amígdala cerebral a todos los estímulos emocionales. Esto sugiere que el entrenamiento de la meditación consciente redujo la reactividad emocional, el cual es consistente con la hipótesis general de que la práctica de meditación reduce el estrés percibido y mejora la estabilidad emocional”, dijo Desbordes a La Gran Época.

En el grupo de meditación compasiva, el contenido emocional positivo llevaba a resultados de escaneo cerebral similar, pero los participantes que meditaban más, reportaron un incremento de actividad en la amígdala en respuesta a imágenes de personas en varias situaciones de sufrimiento.

"Creemos que estas dos formas de meditación cultivan distintos aspectos de la mente", dijo Desbordes en un comunicado de prensa. "Ya que la meditación compasiva está diseñada para aumentar sentimientos de compasión, tiene sentido que pueda incrementar la respuesta de la amígdala al ver gente sufriendo".

"El aumento de la actividad de la amígdala también estaba correlacionada con las puntuaciones de depresión disminuyentes en el grupo de meditación compasiva, que sugiere que entre más compasión se tiene hacia los demás también puede ser beneficioso para uno mismo”, agregó ella. No se observó ningún efecto en el tercer grupo de control. “En general, estos resultados son consistentes con la hipótesis general de que la meditación puede provocar cambios duraderos y beneficiosos en la función cerebral, especialmente en el área de procesamiento emocional”, dijo ella en el comunicado.

Los investigadores concluyeron que la meditación impacta el proceso emocional durante la vida diaria, no solo durante la práctica de la misma y que puede resultar en el desarrollo de ciertos hábitos positivos a largo plazo.

Ecoportal.net

La Gran Epoca

http://www.lagranepoca.com/

26/12/13 Por Arshdeep Sarao

Neurólogos de los Estados Unidos descubrieron recientemente que ocho semanas de meditación en compasión pueden producir cambios cerebrales a largo término y desarrollar rasgos positivos en la personalidad. El equipo encontró que la meditación mejora la estabilidad emocional y la respuesta al estrés alterando la actividad de la amígdala-una región cerebral involucrada en regular las emociones y la atención.

“Este estudio contribuye a un creciente cuerpo cada vez mayor de la evidencia de estudios científicos, que la práctica de la meditación afecta al cuerpo y el cerebro de maneras mensurables”, afirmó la doctora Dr. Gaëlle Desbordes, del Hospital General de Massachusetts, a La Gran Época vía email. Para estudiar los efectos de la meditación, participantes adultos fueron entrenados durante ocho semanas en la meditación compasiva o meditación consciente (para desarrollar la conciencia de la respiración, del pensamiento y las emociones). A un tercer grupo de control se les impartió educación de la salud.

Tres semanas antes y después del entrenamiento, los cerebros de los participantes fueron escaneados mientras observaban una serie de imágenes con distinto contenido emocional.

El grupo de meditación consciente mostró una reducción en la activación de la amígdala cerebral a todos los estímulos emocionales. Esto sugiere que el entrenamiento de la meditación consciente redujo la reactividad emocional, el cual es consistente con la hipótesis general de que la práctica de meditación reduce el estrés percibido y mejora la estabilidad emocional”, dijo Desbordes a La Gran Época.

En el grupo de meditación compasiva, el contenido emocional positivo llevaba a resultados de escaneo cerebral similar, pero los participantes que meditaban más, reportaron un incremento de actividad en la amígdala en respuesta a imágenes de personas en varias situaciones de sufrimiento.

"Creemos que estas dos formas de meditación cultivan distintos aspectos de la mente", dijo Desbordes en un comunicado de prensa. "Ya que la meditación compasiva está diseñada para aumentar sentimientos de compasión, tiene sentido que pueda incrementar la respuesta de la amígdala al ver gente sufriendo".

"El aumento de la actividad de la amígdala también estaba correlacionada con las puntuaciones de depresión disminuyentes en el grupo de meditación compasiva, que sugiere que entre más compasión se tiene hacia los demás también puede ser beneficioso para uno mismo”, agregó ella. No se observó ningún efecto en el tercer grupo de control. “En general, estos resultados son consistentes con la hipótesis general de que la meditación puede provocar cambios duraderos y beneficiosos en la función cerebral, especialmente en el área de procesamiento emocional”, dijo ella en el comunicado.

Los investigadores concluyeron que la meditación impacta el proceso emocional durante la vida diaria, no solo durante la práctica de la misma y que puede resultar en el desarrollo de ciertos hábitos positivos a largo plazo.

Ecoportal.net

La Gran Epoca

http://www.lagranepoca.com/

domingo, 29 de diciembre de 2013

Victor Serge

Victor Serge: “Every revolution is a sacrifice of the present to the future”

Posted by Liam O'Ceallaigh on Saturday, November 16, 2013

“To

all that is terrible in the words “civil war”, “dictatorship”,

“intolerance”, “terror”, must be added the unleashing of anti-social

instincts, the almost total cessation of scientific and artistic

production, an apparent regression in morality, abuses of all sorts;

just think of the victims, victims too many too count.

“But others have said it before us: the

more violent the storm, the shorter it will be. How many are the victims

of the social peace that exists under capitalism? By poverty, by social

diseases (tuberculosis, syphilis, alcoholism, crime, prostitution), by

economic and moral crises, how many lives does it sacrifice

(imperceptibly, for we are used to living in a poisoned atmosphere)

every single day to the domination of the rich? As for wars, an

inevitable consequence of the capitalist system, how many victims do

they create? Certain single days of slaughter in the recent war [World

War I] may have cost humanity more lives than were lost by three years

of revolution in a country of 140 million inhabitants.

“Every revolution is a sacrifice of the

present to the future. What is at stake is the future of humanity. Made

necessary by the previous economic and psychological revolution, this

sacrifice conditions future progress. And it would be wholly accurate to

say that it does not add to the total of the victims of what is called

order, of what is in reality domination, both hypocritical and violent,

by powers of conservatism. For none of those who fall on the road of

revolution—none, except a few privileged people who belong to the ruling

class—would have been spared by poverty, by war, by the calamities of

the capitalist order.” – Victor Serge, “The Anarchists and the Experience of the Russian Revolution”

http://www.walkingbutterfly.com/2013/11/16/victor-serge-every-revolution-is-a-sacrifice-of-the-present-to-the-future/

sábado, 28 de diciembre de 2013

Multinacionales

Las multinacionales no tienen desperdicio

27/12/13 Por Javier Guzmán

Grandes corporaciones convierten el despilfarro de alimentos en el nuevo “trending topic” del marketing social corporativo. Los datos actuales de desperdicio alimentarios son un escándalo ético y moral. Los últimos estudios realizados en la UE estiman que se pierden o desperdician en Europa, entre un 30% y un 50% de los alimentos sanos y comestibles a lo largo de todos los eslabones de la cadena agroalimentaria hasta llegar al consumidor. La generación anual de pérdidas y desperdicios alimentarios en los 27 Estados miembros es de unos 89 millones de toneladas, o sea, 179 kilos por habitante, y ello sin contar los de origen agrícola generados en el proceso de producción ni los descartes de pescado arrojados al mar.

La propia FAO señala en su informe sobre desperdicio alimentario, que en el año 2007 la tierra cultivada para generar desperdicio era de 1,4 billones de hectáreas, es decir un 28% de las tierras cultivables a nivel mundial, en un momento histórico donde cada vez hay más presión sobre este recurso por fines no alimentarios como son los agrocombustibles o la simple especulación financiera.

En el estado español no somos una excepción, tiramos anualmente 2,9 millones de toneladas de alimentos, y como contraste, según Cáritas, en España 9 millones de personas viven en situación de pobreza (menos de 6.000€al año).

Está situación de alguna manera ha hecho sonar las alarmas en el Parlamento de la UE que en año 2012 aprobó una resolución instando a los estados a iniciar estrategias de reducción del 50% del desperdicio para el año 2050, y a esto corresponde el aluvión de campañas para la reducción del despilfarroalimentario, entre ellas la lanzada por el Ministerio de Agricultura, y sorprendentemente las puestas en marcha por las grandes corporaciones agroalimentarias y de distribución que están invirtiendo una gran cantidad de recursos.

Campañas que a priori a todo el mundo nos parecerían justas, necesarias y veríamos con buenos ojos a las empresas que las impulsan, y este objetivo parece que lo han logrado.

Pero si leemos la letra pequeña, veremos que se tratan de campañas que comparten objetivos y elementos comunes, principalmente esconder deliberadamente la responsabilidad de la actual industria agroalimentaria en la generación de cantidades nunca conocidas dedespilfarro alimentario. Intentado hacernos creer que el actual desperdicio alimentario no es una consecuencia del modelo agroalimentario impuesto por grandes corporaciones los últimos años.

La principal línea argumental de todas ellas se trata de dejarnos bien claro que el principal culpable del despilfarro obsceno a nivel global es el consumidor. Un consumidor que compra de más, que no sabe aprovechar productos, que no lee las fechas de caducidad, y que es despilfarrador por naturaleza. Un consumidor irresponsable al que hay que educar y hacer cargar con todas las culpas de la cadena alimentaria, tratándonos como una mezcla de devoradores compulsivos y estúpidos de solemnidad.

Así nos encontramos en el folleto del propio Ministerio de Agricultura que en su primer consejo nos dice: “Elige los productos según las necesidades de tu hogar. Antes de planificar la compra, comprueba el estado de los alimentos que tienes en casa, sobre todo los productos frescos o con fecha de caducidad. Planifica los menús diarios o semanales teniendo en cuenta el número de personas que van a comer.”

Pero, ¿realmente somos los consumidores los grandes culpables de este desastre? ¿Las grandes empresas y gobiernos no tienen nada que ver?

Seguramente los consumidores tenemos mucho que ver, pero si cambiamos el foco de dirección y apuntamos a la industria y sus estrategias empezaremos a ver los contornos de una responsabilidad inmensamente mayor.

Responsabilidad en términos de cantidad, la Eurocámara insiste en que “los agentes de la cadena alimentaria” son los primeros implicados: la industria aporta un 39% de los residuos, mientras restaurantes, caterings y supermercados son responsables de un 14% y un 5% del total, mucha de la cual las propias empresas, gobiernos y lobbies alimentarios han denominado como “inevitable”.

Responsabilidad en el tipo de consumo final pues la mayor parte del despilfarro en casa es debido a la forma de empaquetar losalimentos, descuentos, 2X1, y otras estrategias de grandes cadenas de supermercados que los últimos años han sustituido el comercio de proximidad y determinan nuestro consumo. Si no lo creen, solo tienen que ver que en nuestro país el 80% aproximadamente de las compras de alimentos hoy día se realizan a través de los supermercados, hipermercados y tiendas de descuentos y , pasando de 95.000 tiendas en 1998 a 25.000 en el 2004. Por tanto cada se cierra más el embudo del consumo bajo una falsa apariencia de diversidad

La segunda línea argumental, es que las empresas deben y se comprometen a mejorar la eficiencia de todo el proceso, mejorar cadenas de frío etc..., pero donde ya advierten que hay poco margen, ya que actualmente hacen todo lo posible. En cambio sí pueden sumar un eslabón más a la cadena… y lo han hecho.

Así otro de los elementos comunes de estas campañas es integrar a los bancos de alimentos en la cadena agroalimentaria. De esta forma matan dos pájaros de un tiro, mejorar la imagen de la empresa y ahorrar costes en el tratamiento de residuos.

Una estrategia que se sirve de “cronificar” un tipo de intervención asistencial y de emergencia temporal como son los bancos de alimentos para convertirlo en un elemento más y “normalizado de la cadena”, olvidando por tanto que este tipo de intervenciones genera estigmatización social y en muchas ocasiones la oferta alimentaria no es adecuada, con ausencia de alimentos frescos, con alimentos procesados, pobre en micronutrientes y desproporcionada en energía, grasas saturadas e hidratos de carbono refinados, favoreciendo enfermedades cardiovasculares, diabetes etc….

Sin embargo estás campañas pasan de puntillas por un elemento central para la propia UE o la FAO, para la reducción de despilfarro alimentario como es la apuesta por la agricultura local y los circuitos venta de proximidad.

La apuesta por este otro modelo de producción y consumo evita el desperdicio en todas las fases de la cadena, en la fase de producción principalmente porque no está sujeta a los cánones de la agroindustria y donde la diversidad es un valor frente a la “homogenización” impuesta en distribuidoras y mayoristas.

En la fase de distribución porque no necesita enormes cadenas de frío y de transporte para llegar al consumidor.

Por último, porque la venta directa mejora la adecuación de la oferta y la demanda, al consumir exactamente lo que se necesita.

Además la propia UE reconoce que este tipo de modelo tiene otros grandes beneficios, como son la generación de precios dignos para las personas productoras y, generación de empleo de forma directa e indirecta, dinamización de los territorios y revalorización del mundo rural, incremento en general en la calidad nutritiva de los alimentos, etc..

Por esto, en otros países de Europa, llevan años apostando por este modelo, entre ellos Francia, donde ha desarrollado diversas estrategias para la promoción de la producción y transformación local, iniciativas legislativas como es la adaptación de la legislación higiénico-sanitaria a las características de la pequeña producción e iniciativas directas como es que la compra pública de alimentos de escuelas, hospitales, universidades, etc.. provenga de la agricultura y ganadería local, y convirtiendo el desarrollo de la agricultura de proximidad en uno de los pilares centrales de su estrategia contra el despilfarro.

En nuestro país nada de estás políticas tienen lugar, siendo muy esclarecedor si comparamos el dato de venta directa realizada por agricultores, llegando en Francia a un 20% y en España apenas un 3%.

Como dicen estas campañas, en cuestión de despilfarro alimentario todos somos responsables y todos tenemos algo que hacer, pero también tenemos que decir claramente que no todos somos igual de responsables, y que justamente estás campañas lejos de exigir responsabilidades a los grandes culpables de esta situación, los eximen y ocultan, cuando no, simplemente los ayudan a convertir el despilfarro de alimentos en el último "trending topic" marketing social corporativo.

Ecoportal.net

Rebelión

http://rebelion.org/

En el estado español no somos una excepción, tiramos anualmente 2,9 millones de toneladas de alimentos, y como contraste, según Cáritas, en España 9 millones de personas viven en situación de pobreza (menos de 6.000€al año).

Está situación de alguna manera ha hecho sonar las alarmas en el Parlamento de la UE que en año 2012 aprobó una resolución instando a los estados a iniciar estrategias de reducción del 50% del desperdicio para el año 2050, y a esto corresponde el aluvión de campañas para la reducción del despilfarroalimentario, entre ellas la lanzada por el Ministerio de Agricultura, y sorprendentemente las puestas en marcha por las grandes corporaciones agroalimentarias y de distribución que están invirtiendo una gran cantidad de recursos.

Campañas que a priori a todo el mundo nos parecerían justas, necesarias y veríamos con buenos ojos a las empresas que las impulsan, y este objetivo parece que lo han logrado.

Pero si leemos la letra pequeña, veremos que se tratan de campañas que comparten objetivos y elementos comunes, principalmente esconder deliberadamente la responsabilidad de la actual industria agroalimentaria en la generación de cantidades nunca conocidas dedespilfarro alimentario. Intentado hacernos creer que el actual desperdicio alimentario no es una consecuencia del modelo agroalimentario impuesto por grandes corporaciones los últimos años.

La principal línea argumental de todas ellas se trata de dejarnos bien claro que el principal culpable del despilfarro obsceno a nivel global es el consumidor. Un consumidor que compra de más, que no sabe aprovechar productos, que no lee las fechas de caducidad, y que es despilfarrador por naturaleza. Un consumidor irresponsable al que hay que educar y hacer cargar con todas las culpas de la cadena alimentaria, tratándonos como una mezcla de devoradores compulsivos y estúpidos de solemnidad.

Así nos encontramos en el folleto del propio Ministerio de Agricultura que en su primer consejo nos dice: “Elige los productos según las necesidades de tu hogar. Antes de planificar la compra, comprueba el estado de los alimentos que tienes en casa, sobre todo los productos frescos o con fecha de caducidad. Planifica los menús diarios o semanales teniendo en cuenta el número de personas que van a comer.”

Pero, ¿realmente somos los consumidores los grandes culpables de este desastre? ¿Las grandes empresas y gobiernos no tienen nada que ver?

Seguramente los consumidores tenemos mucho que ver, pero si cambiamos el foco de dirección y apuntamos a la industria y sus estrategias empezaremos a ver los contornos de una responsabilidad inmensamente mayor.

Responsabilidad en términos de cantidad, la Eurocámara insiste en que “los agentes de la cadena alimentaria” son los primeros implicados: la industria aporta un 39% de los residuos, mientras restaurantes, caterings y supermercados son responsables de un 14% y un 5% del total, mucha de la cual las propias empresas, gobiernos y lobbies alimentarios han denominado como “inevitable”.

Responsabilidad en el tipo de consumo final pues la mayor parte del despilfarro en casa es debido a la forma de empaquetar losalimentos, descuentos, 2X1, y otras estrategias de grandes cadenas de supermercados que los últimos años han sustituido el comercio de proximidad y determinan nuestro consumo. Si no lo creen, solo tienen que ver que en nuestro país el 80% aproximadamente de las compras de alimentos hoy día se realizan a través de los supermercados, hipermercados y tiendas de descuentos y , pasando de 95.000 tiendas en 1998 a 25.000 en el 2004. Por tanto cada se cierra más el embudo del consumo bajo una falsa apariencia de diversidad

La segunda línea argumental, es que las empresas deben y se comprometen a mejorar la eficiencia de todo el proceso, mejorar cadenas de frío etc..., pero donde ya advierten que hay poco margen, ya que actualmente hacen todo lo posible. En cambio sí pueden sumar un eslabón más a la cadena… y lo han hecho.

Así otro de los elementos comunes de estas campañas es integrar a los bancos de alimentos en la cadena agroalimentaria. De esta forma matan dos pájaros de un tiro, mejorar la imagen de la empresa y ahorrar costes en el tratamiento de residuos.

Una estrategia que se sirve de “cronificar” un tipo de intervención asistencial y de emergencia temporal como son los bancos de alimentos para convertirlo en un elemento más y “normalizado de la cadena”, olvidando por tanto que este tipo de intervenciones genera estigmatización social y en muchas ocasiones la oferta alimentaria no es adecuada, con ausencia de alimentos frescos, con alimentos procesados, pobre en micronutrientes y desproporcionada en energía, grasas saturadas e hidratos de carbono refinados, favoreciendo enfermedades cardiovasculares, diabetes etc….

Sin embargo estás campañas pasan de puntillas por un elemento central para la propia UE o la FAO, para la reducción de despilfarro alimentario como es la apuesta por la agricultura local y los circuitos venta de proximidad.

La apuesta por este otro modelo de producción y consumo evita el desperdicio en todas las fases de la cadena, en la fase de producción principalmente porque no está sujeta a los cánones de la agroindustria y donde la diversidad es un valor frente a la “homogenización” impuesta en distribuidoras y mayoristas.

En la fase de distribución porque no necesita enormes cadenas de frío y de transporte para llegar al consumidor.

Por último, porque la venta directa mejora la adecuación de la oferta y la demanda, al consumir exactamente lo que se necesita.

Además la propia UE reconoce que este tipo de modelo tiene otros grandes beneficios, como son la generación de precios dignos para las personas productoras y, generación de empleo de forma directa e indirecta, dinamización de los territorios y revalorización del mundo rural, incremento en general en la calidad nutritiva de los alimentos, etc..

Por esto, en otros países de Europa, llevan años apostando por este modelo, entre ellos Francia, donde ha desarrollado diversas estrategias para la promoción de la producción y transformación local, iniciativas legislativas como es la adaptación de la legislación higiénico-sanitaria a las características de la pequeña producción e iniciativas directas como es que la compra pública de alimentos de escuelas, hospitales, universidades, etc.. provenga de la agricultura y ganadería local, y convirtiendo el desarrollo de la agricultura de proximidad en uno de los pilares centrales de su estrategia contra el despilfarro.

En nuestro país nada de estás políticas tienen lugar, siendo muy esclarecedor si comparamos el dato de venta directa realizada por agricultores, llegando en Francia a un 20% y en España apenas un 3%.

Como dicen estas campañas, en cuestión de despilfarro alimentario todos somos responsables y todos tenemos algo que hacer, pero también tenemos que decir claramente que no todos somos igual de responsables, y que justamente estás campañas lejos de exigir responsabilidades a los grandes culpables de esta situación, los eximen y ocultan, cuando no, simplemente los ayudan a convertir el despilfarro de alimentos en el último "trending topic" marketing social corporativo.

Ecoportal.net

Rebelión

http://rebelion.org/

viernes, 27 de diciembre de 2013

jueves, 26 de diciembre de 2013

Ruby Bridges

Ruby Nell Bridges was born in Tylertown, Mississippi in 1954, the same year as the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision. Her grandparents were sharecroppers, but like many people in rural areas, Ruby’s family moved to New Orleans in search of better opportunities. Her father worked as a service station attendant and her mother took night jobs to help support the family. They lived in the front part of a large rooming house on France Street in the Florida neighborhood. Like the rest of the Upper Ninth Ward, the Florida area was predominantly working class. While both whites and blacks lived in the neighborhood, residents were segregated by block. Of course the schools were segregated as well; though Ruby lived only five blocks from William Frantz Elementary, she had to walk much further to attend Johnson Lockett, the school reserved for African American students.

By the time Ruby entered kindergarten, five years had passed since the Brown decision, but most Southern states had done nothing to comply with the mandate to integrate schools. On the contrary, most state and local governments actively engaged in a campaign of massive resistance to avoid implementing Brown. In other Southern states, governors had closed down schools rather than integrate them. A poll released in 1960 found that a slight majority of parents in Orleans Parish favored keeping publics schools open in the event of integration. African American students made up 60% of the public school population, and their parents overwhelmingly supported integration. White parents, on the other hand, strongly opposed desegregation; 12,229 white parents surveyed voted for closure, while only 2,707 voted for desegregation. The Orleans Parish School Board announced that it would only consider the opinions of the white parents.

Under order from the US District Court, however, the school board was ultimately forced to comply with token integration.

The Louisiana legislature showed its resistance to the court order by holding several special sessions and passing a whole string of repressive laws: blocking tax money for integrated schools, blocking paychecks for teachers at integrated schools, abolishing school boards or closing schools under desegregation orders, etc. The only member of the state legislature who voted against every single one of those racist laws was Maurice “Moon” Landrieu. The federal courts ruled all of the laws unconstitutional.

“The only member of the state legislature who voted against every single one of those racist laws was Maurice “Moon” Landrieu. The federal courts ruled all of the laws unconstitutional.”

While 137 first grade students applied to the Orleans Parish School Board to transfer to an integrated school, only a handful of girls were selected after a battery of testing and background investigations. The pupil placement law the board used was intentionally designed to weed out most applicants in an attempt to limit the extent of desegregation. Ruby’s father was concerned about the potential repercussions of challenging the status quo, but her mother eventually convinced him that the risks were worth the benefits for their own daughter and for all children.

On November 14, 1960, three students went to McDonogh No. 19, and one student, Ruby Bridges, went alone to William Frantz Elementary. Until the designated morning, the location of the school sites had not been released. Both schools were located in the Ninth Ward, an area with little political influence. Under the escort of federal marshals, Ruby rode to William Frantz Elementary and entered the school building under their protection. All day long, angry white parents removed their children from the school as Ruby and her mother waited in the front office. At the end of the first school day, the crowd outside of William Frantz was larger and louder than it had been that morning as news of Ruby’s attendance spread.

The next day, the White Citizens’ Council held a meeting in the Municipal Auditorium attended by over 5,000 people. The leaders of the meeting called for protests and boycotts to resist integration. On November 16th, crowds marched to the school board building shouting, “Two, four, six, eight, we don’t want to integrate.” The mayor, DeLesseps Morrison, went on television that night to urge an end to the violence, but he also announced that the New Orleans Police Department was not enforcing the federal court order for school integration. Riots broke out after the announcement, and several people were injured. The police arrested 250 people, but almost none of the white rioters were arrested.

The national media covered the school crisis extensively, and over time business leaders began to worry about the economic impact on the city. Eventually many of the elites of New Orleans signed a declaration in support of preserving public education and obeying the federal courts. The declaration was printed in the newspaper one week before the opening of school in September 1961. A new mayor, Victor Schiro, had also been appointed by the city council after Mayor Morrison took a position as a US ambassador. Mayor Schiro pledged to preserve order, and he assigned sixty police officers to each school undergoing integration.

The plan was successful and integration occurred without any major incidents. When Ruby returned to Frantz after summer vacation, the protesters were no longer waiting outside to harass her. Her second grade class contained over twenty other students, and she was no longer the only African American child enrolled in the school. That being said, the token integration consisted of only twelve African Americans in six schools. The pupil placement law ensured that only a handful of African American students would make it through the screening procedure used for transfers. Eventually the Orleans Parish School Board was forced to abolish the pupil placement law and expand integration to the upper grades, but they did so slowly and reluctantly. By 1964, ten years after Brown, only 809 African Americans had entered formerly white schools.

Ruby went on to finish grammar school at Frantz and to attend an integrated high school. After her parents divorced, Ruby’s mother was forced to move the family out of the house on France Street and into the nearby Florida housing project. After graduating from high school, Ruby wanted to attend college, but she did not have anyone to guide her through the process. She later became a travel agent, married, and raised four sons.

In the early 1990s, Ruby’s youngest brother, Milton, was killed in a drug-related shooting. Though the incident was traumatic, it awakened in Ruby a social consciousness about the issues facing children and adults in urban areas. In particular, she began to put her past experiences into perspective. The fight for school integration was hard fought, and it represented an extremely significant milestone in the Civil Rights Movement. Sadly here in New Orleans, as in other cities across the nation, the victory was short-lived. By the time Ruby began to volunteer at her alma mater, William Frantz, it had long since become segregated again. The neighborhood around the school had also deteriorated with increasing poverty and crime rates.

Inspired by her desire to help children achieve their hopes and dreams, the Ruby Bridges Foundation was established. The foundation began taking small steps to achieve a grand vision- to provide children with an equal opportunity to succeed. Appropriately the work began at Frantz, where the foundation started an after-school program featuring multicultural arts classes. Later, a program called Ruby’s Bridges was developed to promote cultural understanding through community service.

miércoles, 25 de diciembre de 2013

Bees

What is it about bees? Three experts discuss why they’re fascinating, why they’re dying and what can save them

Marla Spivak speaks on the beauty and tragedy of bees. Photo: James Duncan Davidson

Marla Spivak: Why bees are disappearingAnd this should be extremely alarming, given that bees pollinate one-third of the world’s crops.

In today’s talk, given at TEDGlobal 2013, Marla Spivak looks at why bees are disappearing. She highlights four reasons — many related to changes in farming practices — and how they interact to tragic end. But beyond that, Spivak wonders: what do these deaths mean for us given that bees, a species our lives are deeply intertwined with, have thrived for over 50 million years?

“This small bee is holding up a large mirror,” says Spivak.

Dennis vanEngelsdorp: A plea for bees “How much is it going to take to contaminate humans?”

Spivak is not the only TED speaker to express deep concern over the declining bee population. In 2008, the second year in row during which a third of bee colonies were found mysteriously dead, Dennis vanEngelsdorp made “a plea for bees.” It’s a very funny talk, but one that looks at the serious issue of why bee colonies are susceptible to disease. Several years later, at TEDxBoston in 2012, Noah Wilson-Rich looked at the potential of urban beekeeping, Noah Wilson-Rich: Every city needs healthy honey beesproviding fascinating evidence that bees appear to thrive in urban areas.

The TED Blog got these three speakers on the phone for a group conversation about the state of bees.

We’re excited to get the three of you together. To start off, I’d love to hear from each of you: what is it that first sparked your interest in bees?

Noah Wilson-Rich: For me, it happened in school. I was pre-med in college, as an undergrad, I think mostly because I really didn’t know all the career options that were out there beyond teacher, doctor, lawyer, fireman and astronaut. So, I was pre-med, and I took this amazing class called “Sociobiology” that was taught by Rebecca Rosengaus, and it just changed my whole trajectory. It opened up this world of social animals and social insects, and then I ended up applying to a PhD program with Philip T.B. Starks at Tufts. That’s where I started working with honeybees. It was the beginning of a great career.

Dennis vanEngelsdorp: For me, it was also as an undergraduate. I was in a horticulture and international agriculture program — I had my own gardening company and I was sure that I was going to run my own gardening company for the rest of my life. I took a beekeeping class, and I remember just being fascinated. We went out and opened the beehives, and I got stung. And there’s a saying in the bee community: You get stung, and it’s in your blood. You know you’re a beekeeper. If I was mechanical at all — if I could use a bandsaw without fear of losing my fingers — I’d be a beekeeper. But I’m better with numbers, so I went the science route. Bees are a passion. I mean you know right away when you open a hive whether this is what you need to be doing.

Marla Spivak: I was also kind of bored and directionless as an undergrad. I picked up a book at the library on bees — and that was it. I stayed up all night reading the book, and by morning I had a career.

NWR: Which book was this?

MS: It’s called Bee’s Ways. It was written by a naturalist, I think in the 1940s. There’s just something in the book that grabbed me, and so I convinced my advisor that I needed to work for a commercial beekeeper. They sent me to New Mexico and I worked for a beekeeper for a semester.

It’s so interesting that all of these moments happened in college.

NWR: It’s time of exploration, I suppose?

DV: Yeah, a conversion moment.

Marla, in your talk, you suggest that the fascination with honeybees is because, not only are their lives intertwined with ours, but in a lot of ways, they’re like us. Could you speak to the ways that bees are like humans?

MS: I actually think it’s that humans aspire to be like bees. I mean, we live in societies, but their society is a lot more coherent. We look up to honeybees as being very efficient and well-organized, and maybe we think our own society should be more like that. I’ll let the other guys speak to that.

DV: I think it resonates with something very deep in our culture, and even goes back to our ancestors. Here’s this creature, and it sort of demands respect because there’s this aura of danger. And yet, there’s this glorious return. I always imagine that if you’ve never tasted anything sweet, tasting honey for the first time is just sort of nectar from the gods. We’ve evolved with bees, and bees have evolved with us at some level. And they’ve always inspired us. I also think it’s connected with our youth — you know, running barefoot through a meadow and getting stung in the toe. It is a rite of passage. And I think we all understand at some level that if that can’t happen anymore, that we’re diminished.

NWR: I’ve been doing some reading back on the history of humans and bees, especially with honeybees, and it’s interesting to learn about how far back our relationship with them goes. We’ve found the first cave drawings dated back to 13,000 years ago. It’s remarkable — I mean, that is many generations. We’re quite intertwined with them. I mean, we first started domesticating bees in Egypt, in boats and barges on the River Nile for agricultural pollination. Thousands of years ago, I think that was around 2400 B.C.

DV: It is really cool. There’s even a honeyguide bird in Africa. You can walk through the savannahs of Africa and this bird will land in front of you, and lead you to a beehive to collect some of the honey, and leave some of the honey for it. It does this for honey badgers too, and it does it for people. That association is long enough that the bird has evolved a behavior to help communicate where hives are.

What does each of you wish the average person understood about bees?

DV: Everyone owes it to themselves to open a colony of bees once. I think some people will realize they are not beekeepers, but I think that they’ll overcome a lot of fear and they’ll be awed. Other people will fall in love. I don’t know anyone who has opened a colony of bees on a sunny beautiful day, and seen all those worker bees toiling together in harmony, and not been awed. It’s awe-inspiring. The more you do that, the more you’re connected — not only with the bees, but with the environment around you. I wish everyone that experience.

NWR: I also think this connection is something worth exploring for every human. We’ve talked a little about the past with bees, but in terms of the future: anybody who likes food likes bees. It’s important that, if you think about urban planning, you think about how to feed all of the people, and how to make the best use of space. With that comes the need for pollinators. It’s the little connections. I like apples and almonds. You’ve got bees to thank for that.

MS: I would also say — we had a big, pesticide bee-kill incident here in Minneapolis yesterday. Two of three bee colonies within a mile of each other — they’re backyard colonies in an upscale neighborhood — thousands of bees twitching dead in front of the colonies. It’s just heartbreaking. I want people to understand that we share this world with many other creatures. Bees are one of them. I would like everybody to know what they need to eat, and how far and wide honeybees will travel to find flowers as food. It’s not acceptable to contaminate their food source. And it’s not acceptable to contaminate our own food source, though bees are the ones showing it right now.

NWR: I want to add the term ‘bioindicator’ to this conversation. Die-off events that happen, they’re a message that something is off in the natural environment that we need to listen to.

DV: It’s a really good point, and I wonder whether what we need to do is have a cultural revolution. We need to change the way people think. We need to start looking at our environment really differently. The rose with the perfect leaves: that’s beautiful, but in a way that’s also disgusting, because maintaining those ornamental bushes that are perfectly shaped is hugely costly to the environment. We need to start looking at perfectly-mowed green lawns as archaic signs of a past colonial age. What we need is to have a huge bunch of variety there — we need to have native trees that support native caterpillars that support native pollinators and native birds. I think it really requires us to start looking around and becoming disgusted when we see these symbols that are supposed to signal opulence. They’re not, they’re just symbols of death.

MS: It’s really true. We overuse pesticides. We overuse antibiotics. We’re trying to get rid of all the little pesty things that bother us, but in the process we’re killing off all kinds of beneficial insects and all kinds of beneficial microbes. We’re past the tipping point on these things, and the bees are the ones that are telling us that we’ve gone too far.

DV: Everyone can do a little bit and the additive effect would be amazing. If everyone were to transform 10% of their backyard into native habitat, that would have a huge, significant impact.

NWR: Many people come to me and say, “I wish I could do something, but I can’t have bees in my apartment.” I say, “There are many things you can do without actually having to have bees on your property. Creating habitat is a huge benefit. Just planting things on your property helps.” Anybody can do that.

How do you make sure that you’re planting flowers that would be good for bees? Are there good resources for figuring out what would be good in your area?

MS: There are becoming good resources, but it’s even easier than that. Take a walk around and look at the flowers. If you see bees on them, plant those. There are a lot of native plant lists, and then there are a lot of other flowers that bees really, really like. If you stand in front of a bunch of flowers for 30 seconds, and all of a sudden bees start appearing, that’s a good flower.

DV: I do that too, Marla. When I go to the garden center in the spring, I’ll just knock the flowers and see if even those tiny little stingless bees fly out. You’re not just looking at honeybees, but you’re looking at any insects flying off the bloom because there’s a good chance that those are pollinating insects. It’s can be just this beautiful cloud. Some of these bees are so beautiful — I mean, some are like these emerald green jewels. They’re nearly as beautiful as the flowers themselves.

NWR: There’s also a very simple and fun science experiment that anybody can do at home, and based off of this website called the Great Sunflower Project. Just sit by a flower — any flower — for 10 minutes or so. Bring a pen and notepad, and write down how many bumblebees come, how many honeybees. If you don’t know what the insects are, draw them.

What other things can the average person do that would be good for bees?

NWR: You can also hang pieces of bamboo — create hollow crevices that can become an area for native bee species, or solitary bee species, to nest in.

MS: There are so many wild bees out there — I just wish people paid more attention to them. In the world, there are about 20,000 species of wild bees. In the United States, about 4,000 species. And so, like today, when there was this pesticide kill and we saw three honeybee colonies with thousands of dead, it makes me wonder: how many other bumblebees and digger bees and those beautiful emerald sweat bees that Dennis was talking about are probably dead in a field somewhere? So planting flowers is first. But second is paying very careful attention to pesticide use, and asking question before you grab the bottle. “Do I really need this? What’s in this stuff? Does this kill bees?”

NWR: At least here in Massachusetts, we’ve been having some protests about spraying pesticides out in the greater environment. Entire towns are sprayed. It’s a bit reminiscent of the DDT sprayings decades ago — it’s still happening, they’ve just changed up the chemical. That’s something that people should be aware of and perhaps question.

DV: Furthering that thought, let’s make meadows and not lawns. Buying local honey is also a really great way of supporting your local beekeepers. It’s also the most ethical sweetener, because it takes the least amount of carbon to get to your table. Becoming a beekeeper or supporting local beekeepers is something you can do as well.

NWR: There’s also a non-profit that I helped start called ClassroomHives.org that provides information for how to get observation hives inside classroom. We’ve been pretty successful in Boston, but I think if you start educating students when they’re very young — it helps.

DV: When we first saw colony collapse disorder, we defined it with a very specific set of symptoms. I think that the term has been used more broadly to mean any colony deaths, which was never our intent. So, have we seen high levels of losses since CCD first appeared? Yes. Clearly just as high or higher. We didn’t find colony collapse disorder last winter per se, by our definition. But I think the conversation really is about: why are bees dying? I think what we all hoped, naively at the beginning, that we would find one culprit. It’s pretty clear that that’s not the case — there are lots of different culprits that interact. It’s a complicated problem. I think it’s fair to say that we’re making incremental steps in understanding that bees are being challenged by a whole bunch of things. We’ve mentioned insecticides. There’s a lot of evidence now that suggests fungicides, too, may be playing a role. The habitat loss. So we’re seeing that it’s a complex network of problems, which means the solution is also going to be complex. We are making incremental improvements in our understanding, but it’s going to be a long-term undertaking. It’s not one day we’re going to wake up and go, “Aha, we’ve solved the problem.”

What questions do you guys have for each other?

MS: Dennis, how are you going to stop ethanol subsidies? The Farm Bill now has ethanol subsidies, but it doesn’t help conserve land anymore. Corn growers are able to grow corn on marginal land, and they have subsidies and crop insurance where, even if there’s no yield on that land, they’ll get money. So they’re plowing up land that really shouldn’t be cultivated — usually land that has a lot of weeds or flowers on it that bees are using. Bees get deprived of food. It’s the same with large-scale food crops. And not just almonds, which I gave as an example in my talk — but blueberries, cranberries, any crops grown in large monocultures. They’re using herbicide to get rid of the weeds around them. Any time you use an herbicide, you’re killing off flowering plants that bees are using.

DV: It’s tricky, because these things make a lot of money, so meadows are getting plowed into habitat that’s not good for bees. People don’t get paid for coming to your lawn and sowing flowering plants. They get paid for coming in and spraying herbicides and killing plants. We’re in a capitalistic society, so how do we make it to the economic advantage to make sure that we’re leaving room for pollinators? Because clearly, the long-term benefit is there.

MS: You have to have incentives — instead of the incentive for planting corn on marginal land, make an incentive for planting prairie flowers and grasses so that you prevent soil erosion and provide habitat for pollinators. It’s got to be through incentives but, boy, I think we’re many years away from that.

DV: You can get a ticket for not mowing your lawn, but maybe we need to have incentives for people not to mow their lawn.

MS: That’d be great. I just burned off my lawn last year, and planted this prairie of flowers. I got a citation from the city of St. Paul. So I weed-whacked it down to nine inches, and I put up a big sign that says ‘Pollinator Habitat.’ I think the sign helped. This summer, a lot of the flowers came up, so it actually looks intentional.

The TED office is in New York City, where it’s become cool to keep bees. Noah, since you deal with urban beekeeping: are you invigorated by that? Is this part of the cultural change we’re looking for when it comes to bees?

NWR: Absolutely. I was just in New York City at the Intercontinental Times Square Hotel, where we went to the rooftop and got a tour of their beehive. The Times Square honey was delicious. It’s interesting — people do urban beekeeping for many different reasons, from the marketing benefit for larger companies, to just having something to look after and get a sense of agriculture in a place that’s otherwise stressful. It has definitely been a trend. Beekeeping has become so popular in New York, that there’s even talk about now putting a moratorium on new beehives. But this is actually much more than a trend. If we listen to the bees and how they’re doing, they actually prefer cities. In urban areas, they tend to make more honey. In at least the city of Boston, they also survive the winter better. So I think that even though it seems very trendy right now, it will be much more long-lasting.

MS: There’s success, but there’s high risk too. The use of pesticides in cities is not as tightly regulated as it is in agricultural landscapes. And so homeowners, park keepers, anybody in the city can use much higher concentrations of pesticides and insecticides much more frequently than they are, really, allowed by label in agricultural settings. So we really need to be really careful putting bees in cities.

NWR: One of the benefits of being a little independent bee lab is that we can fund our own research. We’re actually participating in a study, with the Harvard School of Public Health, where we’re sampling pollen from beehives all throughout Massachusetts. What my lab is doing is the greater Boston area. We don’t have the data in yet, but it’s an ongoing study to see what the pesticide levels are here compared to more rural, agricultural areas and the suburbs. Surely, it’s going to vary geographically with the pests that are trying to be controlled. It’s really a cost-benefit analysis.

To wrap things up, would each of you share a fact about bees that still boggles your mind?

NWR: Do you know how many eyes bees have? They have five eyes — two compound eyes, and then three ‘ocelli,’ or simple eyes. The compound eyes have many different components that give them some color information, and then the ocelli give a kind of light or dark contrast. I think that’s so cool.

DV: I could talk for days about the anatomy of a bee. I think that one of the things that strikes me about bees is that you often think about evolution as being this competitive thing. But bees are a testimony that sometimes evolution occurs as a dance. We have flowering plants because we have bees, and we have bees because we have flowering plants. This evolutionary dance has created beautiful blooms. I mean, these were the first advertisements — the ultraviolet markings said to bees, ‘Come here and visit me.’ The flowers produce all this pollen and nectar for the bees to bring back. Meanwhile, the bees live in these social constructs that have evolved ways of existing so that they can find the flowers efficiently. The dance that’s occurred between flowers and bees — I find it awe-inspiring.

MS: I don’t know if I can choose one! I think maybe bees’ healthcare system. They bring substances, like resins for example, into the nest that help the overall colony health. They actually go shopping for medicines with antimicrobial properties. And one other really hopeful thing I’ll end with: there’s still so much we can learn about bees.

martes, 24 de diciembre de 2013

Your Own Medicine

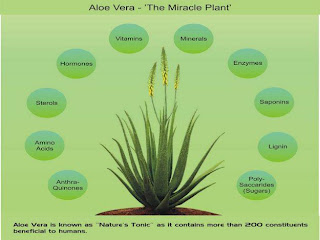

Health Benefits of Aloe Vera: Grow Your Own Medicine

It’s believed the plant we know today as aloe vera first came from Northern Africa.

It’s believed the plant we know today as aloe vera first came from Northern Africa. The first known documentation of its medicinal use was in the ancient Egyptian Papyrus ebers, which provided twelve different recipes for aloe healing.

Since then, the succulent plant has been used across the globe as both an ornamental plant, and more importantly, as a healing medicine. Today, we know the health benefits of aloe vera to range far and wide, from reducing wrinkles to soothing burns.

Aloe vera is one of the easiest houseplants to grow. It requires little in the way of care—simply an occasional watering, warm conditions, and (depending on who you ask) a bit of fertilization now and then. And with this easily grown plant in your home, you are opening yourself to a wealth of medicinal uses. For many, the path to herbalism at home begins with the aloe plant.

The plant has thick, gel-filled leaves which can be easily harvested. Simply slice open one of the leaves and scrape or squeeze out the gel for any one of the following benefits:

Health Benefits of Aloe Vera: Topically

- Soothes burns (one of the best home remedies for sunburns)

- Heals wounds

- Calming acne and eczema

- Use it to calm rashes, boils, and other skin afflictions

- Anti-itching for bug bites

- Use it to reduce wrinkles

- Condition hair using it as a shampoo (may possibly even prevent baldness)

- Use it to moisturize skin

- Apply as a shave gel

Health Benefits of Aloe Vera: Taken Internally

- Soothe stomach upsets and digestive disorders like IBS, constipation, bloating, and colitis

- Reduce indigestion and heartburn

- Use it to stabilizes blood sugar

- Promotes healthy gums

- Improves the body’s immune function

- Promotes the growth of white blood cells and healthy cells in cancer patients

- Strengthens the heart and enriches the blood

- Encourages urinary health

- Reduces arthritis inflammation

You don’t have to look far for new studies coming out about additional benefits of this plant. While you can purchase the juice at health food stores, homegrown gel is not only cheaper, it might be safer.

It’s recommended that you use the largest and most mature leaves to get the most benefits. These leaves are said to contain a greater concentration of helpful gel.

Turn away from pharmaceutical treatment and experience the many benefits of aloe vera today!

lunes, 23 de diciembre de 2013

Stephen King

“Me avergüenzo de ser estadounidense”

Convencido de que pasará a la segunda división de la historia literaria, va ganando, a su pesar, prestigio entre las élites.

Entre la era Ford y la de Obama, ha trazado el fresco del miedo en el hombre medio americano y para el resto del mundo. Pero él no se da la más mínima importancia.

Stephen King ha escrito cerca de 50 novelas y ha vendido más de 300 millones de ejemplares. El autor de Carrie (1973) y El resplandor (1979), el libro que Stanley Kubrick y Jack Nicholson convirtieron en una memorable película, es seguramente el escritor vivo más popular del mundo. Símbolo y metáfora de la cultura pop estadounidense y encarnación demócrata del sueño americano, King es, sin embargo, un tipo absolutamente humilde, un histrión tierno y simpático que tiende a minimizar su talento de escritor y que se toma el pelo a sí mismo sin parar, en un ejercicio que a veces parece sano y otras parece rozar el masoquismo.

Acaba de pasar por París por tercera vez en su vida para promocionar su última novela, Doctor Sueño (Plaza & Janés), que es una especie de secuela o pieza separada de El resplandor. Alojado en el lujoso hotel Bristol, ha paseado por la ciudad, ha dado una rueda de prensa masiva, ha hecho reír a miles de lectores en el inmenso teatro Rex, donde acababa de tocar Bob Dylan, y no ha parado de firmar ejemplares y de hacer amigos contando anécdotas y riéndose de su sombra. El autor deMisery ha contado que llevaba 35 años preguntándose qué habría sido del protagonista de Doctor Sueño, que no es otro que Danny Torrance, el niño que leía el pensamiento ajeno y que sobrevivía a duras penas a los ataques violentos de su padre alcohólico y abusador, Jack Torrance, en aquel hotel triste, solitario y final donde transcurría El resplandor.

Danny tiene ahora casi 40 años, le pega al trago como papá, acude a las sesiones de Alcohólicos Anónimos y cuida a ancianos que están a punto de morir. De ahí el título de una novela que es un compendio del potente universo de King: hay vampiros que comen niños para alimentarse, gente con poderes paranormales, tiroteos, rituales satánicos y sesiones de telepatía intensiva. No se pasa un miedo cerval como en El resplandor, pero es una muy legible novela de acción.

En un reciente artículo publicado en The New Yorker, Joshua Rothman ha explicado que King es el principal canal por donde fluyen todos los subgéneros de la mitad del siglo XX: ciencia ficción, terror, fantasía, ficción histórica, libros de superhéroes, fábulas posapocalípticas, western, que luego traslada a su pequeño reducto de Maine, el remoto Estado del noreste de EE UU donde vive, poblado por 1,2 millones de personas.

La prueba de su influjo en la cultura estadounidense son el cine y la televisión, que siguen rifándose sus historias. Aunque a los 65 años King sigue insistiendo en que lo que escribe no vale gran cosa, cuatro décadas de oficio y una legión de lectores en todo el mundo han acabado convenciendo a una parte de la crítica y a algunos compañeros de profesión de que su literatura pensada para entretener a la América rural pobre tiene más interés, sentido y calidad de la que él mismo cree.

En 2003, King ganó la Medalla de la National Book Foundation por su contribución a las letras americanas, un año después de que lo hiciera Philip Roth. Aquel día, el escritor Walter Mosley destacó su “casi instintivo entendimiento de los miedos que forman la psique de la clase trabajadora estadounidense”. Y añadió: “Conoce el miedo, y no solo el miedo de las fuerzas diabólicas, sino el de la soledad y la pobreza, del hambre y de lo desconocido”.

Pero sobre todo lo demás, King es un personajazo. Fue hijo de madre soltera y pobre, mide casi dos metros, es desgarbado y muy flaco, tiene una cara enorme, habla por los codos, no para de decir tacos, se ha metido varias cosechas de “cerveza, cocaína y jarabe para la tos”, toca la guitarra en una banda de rock con amigos, tiene una mujer católica “llena de hermanos”, tres hijos, cuatro nietos, una cuenta llena de ceros, ha pedido al Gobierno que le cobre más impuestos de los que paga, adora a Obama, odia al Tea Party, hace campaña contra las armas de fuego y es una mina como entrevistado: rara vez se olvida de dejar un par de titulares por respuesta.

¿Así que no le gusta venir a Europa? Vine una vez a París con mi mujer en 1991, y otra a Venecia y a Viena en 1998 con mi hijo; esa vez pasamos una noche por París, pero fuimos a ver una película de David Cronenberg. En Europa paso vergüenza: no hablo otra lengua salvo el inglés, y no me gusta ir dándomelas de celebridad. Prefiero un perfil bajo. Yo vivo en Maine, en un pueblo pequeño donde soy uno más. Cuando vengo a París soy la novedad, nadie me ha visto antes; allí llevan viéndome toda la vida y les da igual; soy el vecino.