x-soldiers asked to give way to Mosley’ was the headline in the Communist Party newspaper, the Daily Worker,

on 30 September 1936. Oswald Mosley, a former Labour Party government

minister, set up the British Union of Fascists in 1932, modelling it on

Hitler’s Nazi Party. Chief among its tactics was the intimidation of

East London’s Jews with marches and rallies, followed by violent

attacks. Mosley announced that he would march through the East End on

Sunday 4 October 1936.

The headline in the Daily Worker was a warning to the

rebellious Stepney Communists who wanted to challenge the fascists where

they marched. The party leadership hated this direct action. They

wanted to draw Communists off to a peaceful march against the Spanish

fascist Franco, which was planned to take place in Trafalgar Square.

On the Thursday, the Daily Worker promised that ‘Sunday will

see columns of London youth marching to Trafalgar Square’. Under the

headline ‘Provocation’, they warned that Mosley’s march could ‘only be

construed as a provocation’. There would be a meeting in Shoreditch Town

Hall that evening, after the two marches, where the Communist leader

Tom Mann would make a token protest against Mosley’s incursion.

The police, the Labour Party and the Board of Deputies of British

Jews also counselled that people stay away from the Mosley

demonstration, for fear of promoting lawlessness.

Stepney Communists thought differently. Forbidden from challenging

the fascists directly by their branch committee, they organised instead

as an ex-servicemen’s association, led by Joe Jacobs. It was they, along

with the radical Independent Labour Party, who organised the opposition

to Mosley, along with many in the local community. Joe Jacobs had his

Communist Party membership suspended for his trouble.

domingo, 29 de enero de 2017

Eric Lomax

'Some time the hating has to stop': A tortured war hero, his Japanese tormentor, and the redeeming power of forgiveness

PUBLISHED: 23:40 GMT, 9 October 2012 | UPDATED: 14:31 GMT, 10 October 2012

Beaten to a pile of broken bones, caged, starved and tortured, Eric Lomax was convinced he would never see Britain ever again.

He had already experienced the lottery of death among the chain gangs on the Burma-Siam Railway. Now things were even worse. Accused of being a spy, he had been left to the mercies of the Japanese army’s secret police.

Among their specialities was what is today known as ‘waterboarding’, when a prisoner undergoes near-drowning. It was surely only a matter of time before he would be put out of his misery.

Ordeal: Eric Lomax (left) was put to work building a railway by his Japanese captors during the Second World War, before he was accused of being a spy and interrogated by Nagase Takashi (right)

As his interrogator had explained to him on arrival at the prison camp in 1943: ‘Lomax, you will be killed shortly whatever happens. But it will be to your advantage in the time remaining to tell the whole truth. You know now how we can deal with people when we wish to be unpleasant.’

And yet Eric Lomax would somehow survive an ordeal so unspeakable that when he was later transferred to Singapore’s notorious Changi prison, he described it as ‘heaven’.

After the war, like so many of those who had survived the atrocities of Japanese captivity, he could barely discuss his experiences with anyone.

He bottled it all up, although he found that tiny things – particularly inaccurate bills or bureaucratic requests for personal information – could almost paralyse him with fury.

Through it all, he retained a loathing for the Japanese, particularly the infernal interrogator still haunting his dreams with the same words: ‘Lomax, you will tell us . . .’

Yet nearly 50 years on, Eric Lomax did something extraordinary. He not only tracked down the man – he met him, befriended him and forgave him. And in 1995, he published a powerful account of his experiences.

Reconciliation: In 2007, Eric Lomax also met Osamu Komai, the son of Captain Mitsuo Komai, who was put to death for his part in the torture of British soldiers

After unimaginable torture and the threat of execution, Lomax described Singapore's Changi jail as 'heavenly'. Pictured are allied prisoners celebrating their liberation from Changi in 1945

Called The Railway Man, it swiftly became a bestseller and won a cluster of literary awards. Indeed, so remarkable is the memoir that it is about to come to the big screen – with Mr Lomax played by Oscar winner Colin Firth, no less – and with Nicole Kidman as his wife.

Sadly, Mr Lomax will not see the film. In the early hours of Monday morning, he died at his home in Berwick-on-Tweed at the age of 93. He leaves a widow and daughter.

But he also leaves an enduring story of the healing power of forgiveness that will be retold long after we are all gone.

Born in 1919, Eric Lomax was the bright, only child of a Scottish Post Office manager and was sent to the Royal High School, Edinburgh.

In 1941, he was posted to Malaya as a young Royal Signals officer. Within weeks, his unit was in headlong retreat to Singapore, where he was taken prisoner in February 1942. He was transported 1,200 miles to start work on the notorious 300-mile ‘death railway’ that the Japanese were constructing in modern-day Thailand and up through the almost impenetrable Burmese jungle towards their cherished military target of India.

For the young Lomax, it was a bitter irony. As a boy, he had been infatuated with railways and engines. As he recalled later: ‘I could not believe I had become a prisoner only to be sent to work on a road for the machines that had given me such pleasure when I was free.’

Powerful: In his book 'The Railway Man' Lomax recorded his experiences working on the Burma railway, similar to those portrayed by Alec Guiness (right) in the film Bridge on the River Kwai

With several brother officers, he ended up working with a team of Japanese railway fitters in Kanchanaburi. It was, he reflected, a relatively civilised berth compared to what others were enduring elsewhere.

‘We were surviving, but that was not enough,’ he wrote. ‘We were rebellious and eager to know what was happening in the war.’ They started taking risks.

Lomax was part of a small group of prisoners who built a radio, bartering stolen tools for parts with local traders. They would tune in to Allied news bulletins from India, and spread word of Allied progress.

At the same time, Lomax was creating a map in the naive hope it might one day be part of an escape plan.

One August day in 1943, however, disaster struck. The Japanese discovered the radio and Lomax and four others were subjected to such sustained pulverising with pick-axe handles that two of them died.

‘I went down with a blow that shook every bone and which released a sensation of scorching liquid pain that seared through my entire body,’ he wrote.

Encouragement: Eric's wife Patti (left) encouraged her husband to get in touch with his erstwhile torturer

Big screen: Eric and Patti Lomax will be played by Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman in a film adaptation of The Railway Man

A prison doctor who examined his body later found not a single patch of white skin on his body between his shoulders and knees.

It was all inflamed and bruised. Worse was to follow days later when he was handed over to the local Kempeitai, or military police. There, he was locked in a 5ft cage that soon became full of red ants, mosquitoes and his own filth.

Periodically, he would be hauled out to face a double act — a shaven-headed NCO, ‘his face full of violence’, and a smaller, ‘almost delicate’ man who spoke English.

The former would do the torturing while the latter did the talking. ‘I hated the interpreter more than the NCO because it was his voice that gave me no rest.’

At the outset, he accused Lomax of ‘anti-Japanese activities’ and issued the news that he would be ‘killed shortly’.

Lomax would remember it as ‘a flat neutral piece of information … I had just been sentenced to death by a man my own age who seemed completely indifferent to my fate. I had no reason to doubt him.’

By now, the Japanese had found Lomax’s secret map and were determined to know why he had it. ‘Lomax’, the little man said again and again, ‘you will tell us.’

Unsurprisingly, his explanation that he had been a train buff and was simply mapping the railway for pleasure failed to convince them.

'Some time the hating has to stop': Eric Lomax met and forgave his torturer

Instead, they tried to force him to confess to espionage with a series of beatings and half-drownings that seemed without end. At times, Lomax ended up crying out for his mother, unaware that she had died soon after his capture (friends put her death down to a broken heart).

‘No one was ever able to tell me how long all this lasted,’ wrote Lomax. He finally came round in his cage. Soon afterwards, he was sent to Bangkok for a Japanese court martial.

To his amazement, he was not executed, but sentenced to five years of close confinement. His response, he says, was one of ‘joy’. The rest of the war would still be spent in brutal conditions, but he would survive it.

'I had proved for myself that remembering is not enough if it simply hardens hate'

And for several decades afterwards, he would get on with life, working in personnel and academia as a lecturer.

He went through the pain of losing a baby son, and a grown-up daughter to a brain illness.

His first marriage broke down and, in 1983, he married Patti, 17 years his junior, whom he had met on a train to Scotland.

Mr Lomax had never had any time for do-gooders preaching the merits of forgiveness. But, with Patti’s encouragement, he finally sought help from a foundation for torture victims and began to address his past.

An old comrade sent him a cutting from an English language paper in Japan. It was about a repentant Japanese soldier who was suffering painful flashbacks and ‘making up’ for his country’s treatment of prisoners of war.

Mr Lomax recognised with astonishment that this was his former interrogator.

For years, he kept tabs on his tormentor – one Nagase Takashi – and even read his memoirs. But it was Patti who finally wrote to Takashi suggesting a meeting.

A long way from home: Actor Jeremy Irvine plays Eric Lomaz in the wartime scenes

Tribute: Colin Firth filming a wedding scene in the adaptation of Eric Lomax's life story

And so it was, in 1993, that the two men were finally reunited on that fabled bridge across the river Kwai. Takashi bowed and, nervously, began a lengthy apology. 'I am very, very sorry,' he told Mr Lomax. 'I never forgot you. We treated your countrymen very, very badly.'

'We both survived,' Mr Lomax replied. And then the two men talked long and hard over the events of 1943.

It was a therapeutic process for both. Later on, Mr Lomax accepted an invitation to visit Takashi in Japan, where he finally, formally forgave him – reading out a letter saying as much. ‘I had proved for myself that remembering is not enough if it simply hardens hate,’ wrote the proud Scot.

And Takashi’s own verdict? 'I think I can die safely now.'

After all he went through in life, perhaps there could be no better epitaph for Mr Lomax than the last line he wrote in his book: 'Some time the hating has to stop.'

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2215357/Eric-Lomax-A-tortured-war-hero-Japanese-tormentor-redeeming-power-forgiveness.html#ixzz3R5NEqDEz

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

sábado, 28 de enero de 2017

PIERRE JOSEPH PROUDHON

PIERRE JOSEPH PROUDHON - Ser gobernado.

“Ser

gobernado significa ser observado, inspeccionado, espiado, dirigido,

legislado, regulado, inscrito, adoctrinado, sermoneado, controlado,

medido, sopesado, censurado e instruido por hombres que no tienen el

derecho, los conocimientos, ni la virtud necesarios para ello. Ser

gobernado significa, con motivo de cada operación, transacción o

movimiento, ser anotado, registrado, controlado, grabado, sellado,

medido, evaluado, sopesado, apuntado, patentado, autorizado, licenciado,

aprobado, aumentado, obstaculizado, reformado, reprendido y detenido.

Es,

con el pretexto del interés general, ser abrumado, disciplinado, puesto

en rescate, explotado, monopolizado, extorsionado, oprimido, falseado y

desvalijado, para ser luego, al menor movimiento de resistencia, a la

menor palabra de protesta: reprimido, multado, objeto de abusos,

hostigado, seguido, intimidado a voces, golpeado, desarmado,

estrangulado por el garrote, encarcelado, fusilado, juzgado, condenado,

deportado, flagelado, vendido, traicionado y por último, sometido a

escarnio, ridiculizado, insultado y deshonrado.

¡Eso es el gobierno, esa es su justicia, esa es su moral!”

Simone Weil

La historia nos reserva a veces pequeñas sorpresas a través de algunas vidas no suficientemente exploradas, que se convierten en objeto de atención para los que viven un momento diferente al suyo. Es el caso de Simone Weil, mujer de firme carácter, cuyo pensamiento nos llega más de un siglo después de que naciera.

Además de ser una de las tres mujeres filósofas más importantes nacidas a comienzos del s. XX, junto con María Zambrano y Hannah Arendt, Simone Weil es la que estuvo más implicada en poner en práctica sus ideales de educación y de justicia para lograr una humanidad más sabia y más libre.

Sus citas, rotundas y certeras, aparecen como referencias a su pensamiento, marcado por un itinerario vital e intelectual que se manifiesta en tres direcciones: una búsqueda continua y apasionada de la verdad, que la lleva a estudiar Filosofía y a interesarse por todas las manifestaciones religiosas; una marcada pureza natural que se asombra ante la contemplación de la belleza del mundo y del arte, en donde presiente la huella de Dios; y una vulnerabilidad ante la desgracia de las clases más desprotegidas de la sociedad, que la llevó a luchar por mejorar sus vidas.

Manuela León

Su nombre es sinónimo de fuerza, coraje, rebeldía. Como mujer y

como indígena fue una de las dirigentes claves en la sublevación

emprendida por Fernando Daquilema en contra del gobierno de García

Moreno y por la reivindicación de sus derechos colectivos.

Manuela León demostró fiereza y aplomo en la batalla. Por eso, fue fusilada el 8 de enero de 1872, una vez que la insurrección había sido aplacada.

La revolución de Daquilema

Fernando Daquilema, nacido en Yaruquíes en 1845, encabezó una sublevación de miles de indígenas en contra del cobro de los diezmos y la exigencia de mano de obra para la ejecución de obras públicas. Daquilema, con 25 años, fue coronado Rey, en un vano intento por recuperar el imperio inca.

El historiador Carlos Ortiz Arellano en el libro “Cien figuras de Chimborazo”, arma una cronología de los hechos, basada a su vez en la investigación de Julio Tobar Donoso y otros documentos.

El levantamiento comienza en Yaruquíes, la tarde del 18 de diciembre de 1871, con el ajusticiamiento de tres comisionados que pretendían reunir gente para trabajar en la construcción de las vías. Los indígenas se ubican en los cerros de Cacha, mientras se preparan el primer informe oficial para el gobierno.

Los levantados cobran la vida de diez personas más, entre ellos Rudecindo Rivera y David Castillo, quienes cumplían la función de diezmeros.

El 19 de diciembre, el gobernador Rafael Larrea Checa envía 50 hombres hacia Yaruquíes, pero regresan a la ciudad ante el considerable número de alzados, uno de los cuales fallece en los iniciales enfrentamientos. Mientras tanto, una facción de indígenas se ubica a la altura de Balbanera.

El 21 del mismo mes, se unen a la insurrección los pueblos de Licto y Cicalpa, y el presidente Gabriel García Moreno decreta el estado de sitio a la provincia de Chimborazo, el cual rige hasta el 13 de marzo de 1872.

Los insurrectos avanzan hasta Punín, donde incendian 14 casas, bajo el mando de Manuela León. Las acciones se mantienen hasta el 24, cuando llegan refuerzos desde Quito.

La tranquilidad vuelve a la zona el 3 de enero de 1872, cuando los “sublevados expresan arrepentimiento ante las autoridades (y se) afirma que Fernando Daquilema (…) se entregó a los soldados en Cacha”.

Inmediatamente comienza el proceso contra los participantes, y por supuesto, los primeros en investigación son los cabecillas.

Manuela León y Julián Manzano son ejecutados el 8 de enero.

En los primeros días de enero, se inicia el proceso contra los cabecillas y participantes de la sublevación.

El 26 de marzo el Consejo de Guerra, por unanimidad, condena a la pena de muerte a Fernando Daquilema.

El presidente de la República revisa el expediente, y finalmente, el 8 de abril, la sentencia se cumple. Daquilema es fusilado en la plaza de Yaruquíes.

El letrero colocado es revelador, e irónicamente similar al que permaneció sobre la cruz de Jesús:

“Ajusticiado por el Ministerio de la Ley por haber recibido el calificativo de Rey y haber sido el cabecilla principal de la sedición de 1871”.

La participación de Manuela

Manuela León nació probablemente en 1840, en la comunidad de Poñenquil del pueblo de Punín, según ha investigado Ortiz Arellano.

Manuela integró el movimiento de Daquilema y participó en el incendio de 14 casas en Punín, el 21 de diciembre de 1871.

La etnóloga Marcela Costales, en su libro “Mensajeras Cósmicas”, se pone en la piel de la dirigente y narra:

En 1871 recibimos en Poñenquil con alborozo, con lágrimas, con fe, con delirante entusiasmo, la grande, la esperada noticia de que se iniciaría la rebelñion indígena de Cacha. Pacífico Daquilema de 41 años y su mujer Juliana Paguay de edad casi similar a la mía, mis vecinos, tomaron la voz del alzamiento y reclamaron el lugar de nuestros cabecillas. Con toda la reciedumbre que me había dado los años, los trabajos forzados en las carreteras nacionales, los tributos y la ofensas diarias, me sumé al grupo de Pashi, “el uto”, llamado así por le faltaba un dedo de la mano derecha.

Manuela León se enfrenta a los soldados, con tal fiereza que vence y da muerte al jefe de las milicias, teniente Miguel Vallejo. De este encuentro, se cuenta que León saca con su tupo los ojos de la víctima.

No obstante, el delirio del triunfo dura poco, y los dirigentes son capturados. El Consejo de Guerra juzga a la rebelde y la condena a muerte. Manuela es ejecutada junto con Julián Manzano. Lo intrigante es que en el expediente constaba el nombre de Manuel León y no de Manuela.

“… el levantamiento de una parte de la raza indígena contra los blancos en la provincia de Chimborazo, a fines de 1871, movimiento que, producido por la embriaguez y la venganza, y manejado con varios actos de salvaje ferocidad, fue contenido fácilmente por la fuerza armada, castigado severamente por la justicia en algunos de los más culpables y completamente apaciguado y extinguido por el perdón concedido a los otros delincuentes”.

Gabriel García Moreno. Mensaje al Congreso en agosto de 1872. Publicado en “El Nacional”, 1873

https://digvas.wordpress.com/2010/05/10/manuela-leon-la-rebelde/

Manuela León demostró fiereza y aplomo en la batalla. Por eso, fue fusilada el 8 de enero de 1872, una vez que la insurrección había sido aplacada.

La revolución de Daquilema

Fernando Daquilema, nacido en Yaruquíes en 1845, encabezó una sublevación de miles de indígenas en contra del cobro de los diezmos y la exigencia de mano de obra para la ejecución de obras públicas. Daquilema, con 25 años, fue coronado Rey, en un vano intento por recuperar el imperio inca.

El historiador Carlos Ortiz Arellano en el libro “Cien figuras de Chimborazo”, arma una cronología de los hechos, basada a su vez en la investigación de Julio Tobar Donoso y otros documentos.

El levantamiento comienza en Yaruquíes, la tarde del 18 de diciembre de 1871, con el ajusticiamiento de tres comisionados que pretendían reunir gente para trabajar en la construcción de las vías. Los indígenas se ubican en los cerros de Cacha, mientras se preparan el primer informe oficial para el gobierno.

Los levantados cobran la vida de diez personas más, entre ellos Rudecindo Rivera y David Castillo, quienes cumplían la función de diezmeros.

El 19 de diciembre, el gobernador Rafael Larrea Checa envía 50 hombres hacia Yaruquíes, pero regresan a la ciudad ante el considerable número de alzados, uno de los cuales fallece en los iniciales enfrentamientos. Mientras tanto, una facción de indígenas se ubica a la altura de Balbanera.

El 21 del mismo mes, se unen a la insurrección los pueblos de Licto y Cicalpa, y el presidente Gabriel García Moreno decreta el estado de sitio a la provincia de Chimborazo, el cual rige hasta el 13 de marzo de 1872.

Los insurrectos avanzan hasta Punín, donde incendian 14 casas, bajo el mando de Manuela León. Las acciones se mantienen hasta el 24, cuando llegan refuerzos desde Quito.

La tranquilidad vuelve a la zona el 3 de enero de 1872, cuando los “sublevados expresan arrepentimiento ante las autoridades (y se) afirma que Fernando Daquilema (…) se entregó a los soldados en Cacha”.

Inmediatamente comienza el proceso contra los participantes, y por supuesto, los primeros en investigación son los cabecillas.

Manuela León y Julián Manzano son ejecutados el 8 de enero.

En los primeros días de enero, se inicia el proceso contra los cabecillas y participantes de la sublevación.

El 26 de marzo el Consejo de Guerra, por unanimidad, condena a la pena de muerte a Fernando Daquilema.

El presidente de la República revisa el expediente, y finalmente, el 8 de abril, la sentencia se cumple. Daquilema es fusilado en la plaza de Yaruquíes.

El letrero colocado es revelador, e irónicamente similar al que permaneció sobre la cruz de Jesús:

“Ajusticiado por el Ministerio de la Ley por haber recibido el calificativo de Rey y haber sido el cabecilla principal de la sedición de 1871”.

La participación de Manuela

Manuela León nació probablemente en 1840, en la comunidad de Poñenquil del pueblo de Punín, según ha investigado Ortiz Arellano.

Manuela integró el movimiento de Daquilema y participó en el incendio de 14 casas en Punín, el 21 de diciembre de 1871.

La etnóloga Marcela Costales, en su libro “Mensajeras Cósmicas”, se pone en la piel de la dirigente y narra:

En 1871 recibimos en Poñenquil con alborozo, con lágrimas, con fe, con delirante entusiasmo, la grande, la esperada noticia de que se iniciaría la rebelñion indígena de Cacha. Pacífico Daquilema de 41 años y su mujer Juliana Paguay de edad casi similar a la mía, mis vecinos, tomaron la voz del alzamiento y reclamaron el lugar de nuestros cabecillas. Con toda la reciedumbre que me había dado los años, los trabajos forzados en las carreteras nacionales, los tributos y la ofensas diarias, me sumé al grupo de Pashi, “el uto”, llamado así por le faltaba un dedo de la mano derecha.

Manuela León se enfrenta a los soldados, con tal fiereza que vence y da muerte al jefe de las milicias, teniente Miguel Vallejo. De este encuentro, se cuenta que León saca con su tupo los ojos de la víctima.

No obstante, el delirio del triunfo dura poco, y los dirigentes son capturados. El Consejo de Guerra juzga a la rebelde y la condena a muerte. Manuela es ejecutada junto con Julián Manzano. Lo intrigante es que en el expediente constaba el nombre de Manuel León y no de Manuela.

“… el levantamiento de una parte de la raza indígena contra los blancos en la provincia de Chimborazo, a fines de 1871, movimiento que, producido por la embriaguez y la venganza, y manejado con varios actos de salvaje ferocidad, fue contenido fácilmente por la fuerza armada, castigado severamente por la justicia en algunos de los más culpables y completamente apaciguado y extinguido por el perdón concedido a los otros delincuentes”.

Gabriel García Moreno. Mensaje al Congreso en agosto de 1872. Publicado en “El Nacional”, 1873

https://digvas.wordpress.com/2010/05/10/manuela-leon-la-rebelde/

Battle of Cable Street

They Shall Not Pass: the Battle of Cable Street 80 years on

This ‘ex-servicemen’s association’ and the ordinary Jews of the East End made the difference. Their slogan, ‘They shall not pass’, captured the moment. Around 3,000 fascists turned up. Twice as many police were mobilised to support their incursion into Jewish neighbourhoods. But around 20,000 were rallied to stop them. Most of the fighting was between the police and the anti-fascists. On police advice, Mosley retreated, and the day was done. It became known as the Battle of Cable Street.

After the event, the Communist Party leadership quickly reversed its edicts against the counter-demo. It rewrote history with Stalinist determination, claiming the mobilisation as its own when in truth it had tried to sabotage it. Local Communist leader Phil Piratin was lauded as the leader of a protest he had precious little to do with.

The House of Commons was worried that ordinary people in the East End would take matters into their own hands and deal with the threat of fascism as they saw fit. The Labour Party’s Herbert Morrison went to see the home secretary Sir John Simon to demand police action. A Public Order Act was rushed through parliament to clamp down on political marches.

Today, many people in power still think of the approach of the Public Order Act, the official banning of disruptive demonstrations, as the best way to pay homage to the anti-fascists of the old East End. In keeping with this approach, left-wing groups passed ‘No Platform’ policies against right-wingers in the 1970s, and radicals still often appeal to the police to ban right-wing demonstrations today.

But the truth is that the Public Order Act was more often used against left-wingers and radicals than against the right. It was used against left-wing counter-demonstrations against fascists, Sinn Fein marches in the 1970s and striking miners in 1984/85.

What was really revolutionary about the Battle of Cable Street was that people took matters into their own hands, instead of obeying the law, the Labour Party or Communist Party officials. If they had opted to follow the instructions of the authorities and the left, Mosley would have marched unmolested through the East End, protected by the police, with the radicals safely on the other side of town. The lesson of the Battle of Cable Street is that communities should always prefer to defend themselves, with solidarity from others, rather than turning to officialdom, the law or Labour to ‘protect’ them, which too often means their independence being limited.

James Heartfield is the author of The European Union and the End of Politics, published by ZER0 Books.

Sources:

Daily Worker, 30 September 1936

Out of the Ghetto: My Youth in the East End, Communism and Fascism, 1913-39, by Joe Jacobs, 1978

Our Flag Stays Red, by Phil Piratin, 1948

Labour Inside the Gate: A History of the British Labour Party Between the Wars, by Matthew Worley, 2009

http://www.spiked-online.com/newsite/article/they-shall-not-pass-the-battle-of-cable-street-80-years-on/18838#.WIz4qtSubow

Countess Markievicz

Countess Markievicz

Countess Markievicz played an active part in the Easter Rising of 1916 and in post-1916 Irish history. Born in 1868 as Constance Gore-Booth, Countess Markievicz was sentenced to death for her part in the Easter Uprising but had the sentence commuted to life imprisonment on account of her gender.

Countess Markievicz

Countess Markievicz was born in London into a wealthy family that had a large estate in County Sligo. Her father, Sir Henry Gore-Booth, was an explorer, but unlike many landowners in Ireland, he treated his tenants with concern. Therefore, Markievicz was brought up in a household that showed care and concern to those on the family estate in Lissadell. Her sister, Eva, would later involve herself in the labour movement in England - and women's suffrage. The future countess did not share, at this time, her sister's aspirations. Constance wanted to be an artist and in 1893, she went to London to study art at the Slade School. In 1898, she continued her studies at the Julian School in Paris. It was here that she met Count Casimir Dunin Markievicz. He was from a wealthy Polish family but was already married when he met Constance. However, his wife died in 1899 and he married Constance in 1901 making her Countess Markievicz.

In 1903, the couple moved to Dublin and the Countess gained a reputation for herself as a landscape artist. In 1905, the Countess founded and funded the United Artists Club which was an attempt to bring together all those in Dublin with an artistic bent. At this moment in time there was nothing tangible to link her to basic politics, let alone a drive for Ireland's independence from British rule. Then in 1906, something happened which pushed the Countess headlong into Irish politics and away from art. In 1906, she rented out a small cottage in the countryside around Dublin. The person who had previously rented it was a poet called Pádraic Colum. He had left behind old copies of 'The Peasant and Sinn Fein'. This was a revolutionary publication that pushed for independence from British rule. The Countess read those publications that were left behind and was taken in by what they wanted.

In 1908, the Countess became actively involved in nationalist politics in Ireland. She joined Sinn Fein and Inghinidhe na hEerann - a women's movement. In the same year, the Countess stood for Parliament. She contested the Manchester constituency where her most famous opponent was Winston Churchill. The Countess lost the election but in the space of two years she had gone from a life oriented around art to a life oriented around Irish politics and independence in particular.

In 1909, she founded Fianna Éireann which was a form of Boy Scouts but with a military input, including the use of firearms. Patrick Pearse said that the creation of Fianna Éireann was as important as the creation of the Irish Volunteers in 1913. In 1911, the Countess was jailed for the first time for her part in the demonstrations that took place against the visit of George V. In the lock-out of 1913, she ran a soup kitchen to aid those who who could not afford food.

When war broke out in August 1914, many in Ireland were happy to support the suspension of Home Rule until the war was over. Thousands of Irishmen volunteered to fight in Britain's hour of need. However, a hard core of people were not prepared to accept this situation and they were willing to use Britain's involvement in the war as an opportunity they could exploit. This led to the Easter Uprising of 1916 and it was almost natural for the Countess to have got involved.

The Countess played a very active role in the fighting that took place in Dublin. Having joined James Connolly'sCitizen Army, she was second in command at St. Stephen's Green. Those who fought there held out for six days and surrendered only when they were given a copy of the surrender order signed by Patrick Pearse. Ironically, the British officer (Capt. Wheeler) who accepted their surrender was a distant relative of the Countess. As with many of the arrested rebels when they were paraded through the streets of Dublin, the Countess was verbally abused by Dubliners who had seen part of their city devastated.

The Countess was not the only women arrested at the end of the rebellion. In total, 70 women were but the Countess was the only one held in solitary confinement at Kilmainham Jail. It is possible that the British authorities believed that by herself she was less of a problem; allowed to socialise with other women at the prison, she might be a source of trouble. However, from her cell the Countess could hear the firing squads. She was brought before a court martial and sentenced to death. She effectively admitted her guilt by saying:

"I did what was right and I stand by it."

|

However, General Maxwell, the officer commanding the court martial procedure, commuted her sentence to life in prison on account of the fact that she was female. When she was told the news, she said:

"I do wish your lot had the decency to shoot me."

|

The Countess was released from prison in 1917, along with others involved in the Uprising, as the government in London granted a General Amnesty for those involved in the Easter Uprising. However, her experiences did nothing to dampen her involvement in politics. In 1918, she was jailed again for her part in anti-conscription activities. While in prison she was elected an MP standing as a Sinn Fein candidate. The Countess refused to take up her seat as it would have involved swearing an oath of allegiance to the king. During the Anglo-Irish War, she was either on the run from the British authorities or she was, once again, in prison. She was a staunch opponent of the 1921 Treaty which gave Ireland dominion status within the British Empire. The Countess referred to those who supported the treaty as "traitors". Michael Collins, the man who signed the treaty, claimed that she could never understand the rationale behind the treaty as she was English.

After the civil war in Ireland, she toured America. The Countess was also re-elected to the Dáil but her staunch republican views led her to being sent to jail again. In prison, she and 92 other female prisoners went on hunger strike. Within a month, the Countess was released. The hunger-strikes of the Suffragettes had been a huge embarrassment to the British government before the war. The newly created Dáil could barely afford a similar scandal. In 1926, the Countess joined Fianna Fáil led by Eamonn de Valera. She died in 1927. It is estimated that over 250,000 people lined the streets for her funeral in Dublin and de Valera read the eulogy.

| "One thing she had in abundance - physical courage; with that she was clothed as with a garment." Sean O'Casey |

MLA Citation/Reference

"Countess Markievicz". HistoryLearningSite.co.uk. 2014. Web.

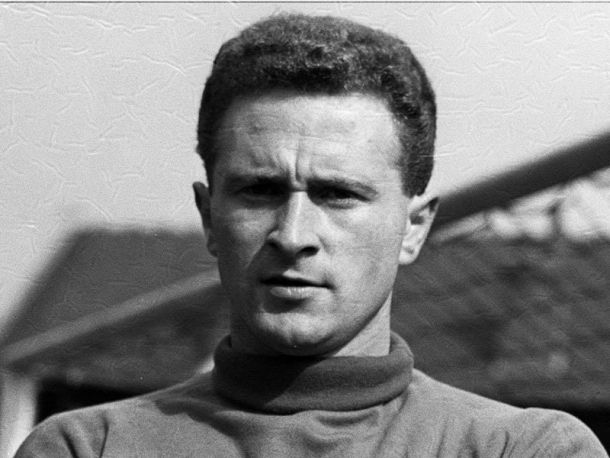

Harry Gregg

Munich Remembered: Harry Gregg, the 'Hero of Munich'

As Manchester United supporters remember those who lost their lives in the tragic events of the Munich air disaster, Harry Gregg will be forever remembered as a hero.

Munich Remembered: Harry Gregg, the 'Hero of Munich'

Born in 1932, Gregg survived the horrendously tragic events of the Munich air disaster, which claimed the lives of countless Busby Babes on 6th February 1958. Despite his immense presence between the sticks on the field, the Northern Irishman should also be remembered for his valour after the crash, returning into the disaster to save teammates, loved ones, and in Gregg’s case, total strangers.

Astonishingly, the goalkeeper never won a medal in the colours of United, but was appointed a Member of the British Empire in 1995.Enjoying a career spanning between 1957 and 1966, Gregg was considered a fairly recent signing at the time of the incident, after breaking the world record fee for a goalkeeper - £23,000 paid to Doncaster Rovers. Astonishingly, the goalkeeper never won a medal in the colours of United, but was appointed a Member of the British Empire in 1995.

The captivating story of his inspirational act is one of the most emotional from the tragic day, as he saved Bobby Charlton, Jackie Blanchflower and Dennis Viollet from the burning aftermath. He also returned to help Vera Lukić, the pregnant wife of a Yugoslav diplomat and her daughter, Vesna, as well as manager Sir Matt Busby, who has suffered substantial injuries before going on to lift the European Cup with the reformed Busby Babes ten years later.

Despite being dubbed the ‘Hero of Munich’, Gregg remains a honourable and humble man, proclaiming he felt any of his teammates would have done the same should they have been in the position of the goalkeeper – who kept 48 clean sheets in his time with the Red Devils. Gregg returned to Manchester and continued in the side, unfortunate to miss the 1963 FA Cup Final due to a shoulder injury.

Bravery is one thing but what Harry did was about more than bravery. It was about goodness.Fellow United great George Best commented on his act of courage, saying, “bravery is one thing but what Harry did was about more than bravery. It was about goodness.” Gregg committed himself to the club from the bottom of his heart, and still does, whether his dominant nature on the field or his modest attitude to his heroic achievements. Even when losing a number of friends aboard the European Airways Flight 609, he showed tremendous resilience and valour to return to the aircraft.

“I am not John Wayne, I have never been John Wayne, I don’t want to be John Wayne,” he said speaking many years after the disaster. Gregg did not want to be known at a hero after losing numerous friends, especially after the heart-rending turn of events for Duncan Edwards, a close friend who looked to have made it until his sudden death 10 days later.

Nevertheless, the ‘Hero of Munich’ can hold his head high for his accomplishment on the tragic day, and should be remembered for his fearlessness as much as those who couldn’t return home.

https://www.vavel.com/en/football/premier-league/manchester-united/447023-munich-remembered-harry-gregg-the-hero-of-munich.html

Simone de Beauvoir

“No se nace mujer: llega una a serlo”, Simone de Beauvoir

Autora de El segundo sexo, texto sobre lo que había significado para ella el ser mujer, Simone de Beauvoir ( París, Francia, 1908) comenzó a investigar acerca de la situación de las mujeres a lo largo de la historia y escribió este ensayo que aborda cómo se ha concebido a la mujer, qué situaciones viven y cómo se puede intentar que mejoren sus vidas y se amplíen sus libertades.

El texto indaga acerca de la vida de la mitad de la humanidad. También es considerada una obra enciclopédica, pues aborda la identidad de las mujeres y la diferencia sexual desde los puntos de vista de la psicología, la historia, la antropología, la biología, la reproducción y las relaciones afectivo-sexuales.

La teoría principal que sostiene Beauvoir es que “la mujer”, o más exactamente lo que entendemos por mujer (coqueta, frívola, caprichosa, salvaje o sumisa, obediente, cariñosa, etc.), es un producto cultural que se ha construido socialmente.

Pensadora y novelista francesa, representante del movimiento existencialista ateo y figura importante en la reivindicación de los derechos de la mujer, Simone de Beauvoir, originaria de una familia burguesa, destacó desde temprana edad como una alumna brillante. Estudió en la Sorbona y en 1929 conoció a Jean-Paul Sartre, filósofo, novelista, dramaturgo, activista político y crítico literario francés, exponente del existencialismo y del marxismo humanista, quien se convirtió en su compañero de vida. Entre ellos hubo un pacto de amor libre, de pareja abierta, en el que se ambos pretendían que la verdad triunfara antes que los celos.

Su obra, expuesta en libros, revistas, ensayos y crítica social, resulta un punto de partida teórico para distintos grupos feministas, y se convirtió en una obra clásica del pensamiento contemporáneo, en especialEl segundo sexo, publicado en 1949, en este texto elaboró una historia sobre la condición social de la mujer y analizó las distintas características de la opresión masculina. Afirmó que al ser excluida de los procesos de producción y confinada al hogar y a las funciones reproductivas, la mujer perdía todos los vínculos sociales y con ellos la posibilidad de ser libre.

Analizó la situación de género desde la visión de la biología, el psicoanálisis y el marxismo; destruyó los mitos femeninos e incitó a buscar una auténtica “liberación”. Sostuvo que la lucha para la emancipación de la mujer era distinta y paralela a la lucha de clases, y que el principal problema que debía afrontar el “sexo débil” no era ideológico sino económico.

Durante su vida, y hasta el final de esta, el 14 de abril de 1986, fue una incansable luchadora por los derechos humanos, no sólo por los femeninos. Realizó críticas, obras de teatro e investigaciones sociales cuyos temas principales fueron: el feminismo, el pensamiento político de la izquierda ante y posguerra (Segunda Guerra Mundial), el psiconanálisis y el existencialismo.

Para la autora “la vida es un largo combate por el que se llega a ser uno mismo, esa es la tarea más elevada e ineludible de todo ser humano”. Todo se construye, incluida la felicidad y, por supuesto, la identidad personal. Abrazó la filosofía de confianza plena a las personas, para sólo otorgar a ellas la responsabilidad de labrar sus propios destinos.

Cultura Colectiva

Los inmigrantes mexicanos que le ganaron al MIT

Hace 10 años un grupo de adolescentes mexicanos participó en una sofisticada competencia robótica submarina, organizada por la NASA, y vencieron a un equipo del Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT, por sus siglas en inglés) y otras universidades prestigiosas en el 2004, la Tercera Competencia de Vehículos Marinos de Tecnología Avanzada Operados por Control Remoto, realizada en el 2004.

Se trata de Lorenzo Santillán (16 años), Cristian Arcega (16), Óscar Vázquez (17) y Luis Aranda (18) –todos traídos a E.U. cuando eran niños por sus familias, algunos de forma ilegal–, estudiantes de una secundaria de Phoenix (Arizona). Ellos decidieron ir a la competencia, algo que ya era visto casi como una locura, pensando que ese ya era su gran logro. La mayoría había entrado al proyecto como una forma de hacer algo en sus ratos libres durante el receso de vacaciones de la escuela pública Carl Hayden.

Ingenio vs. recursos

“Hicimos un robot con tubos de PVC que compramos en Home Depot y los unimos con pegamento, por lo que lo bautizamos ‘Stinky’ (apestoso). Le pusimos cuatro cámaras de video y, en la parte superior, dentro de una caja de herramientas, pusimos los componentes electrónicos”, recuerda Arcega en una conversación con EL TIEMPO, durante la exhibición de su proyecto en la Feria Internacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, que patrocina la firma Intel.

‘Stinky’, un inmenso robot de 50 kg y pintado poco estéticamente de azul, rojo y amarillo, no se parecía en nada a ese aparato pequeño, elegante y compacto diseñado por 12 ingenieros de una de las mejores universidades de E.U. Y no solo eso, el robot de MIT valía 11.000 dólares, nada comparable con los 800 que había costado fabricar el de los cuatro jóvenes mexicanos. Para empeorar las cosas, el día previo a la competencia descubrieron que la caja de herramientas presentaba un pequeño flujo. Si el agua llegaba a las partes electrónicas, estaban perdidos. Y como no había tiempo para repararlo debidamente, a Lorenzo se le ocurrió una solución tan atrevida e ingeniosa que terminó por seducir a los jurados: colocar un tampón en el interior que absorbiera el líquido.

El resultado: los premios en Elegancia en Diseño, Reporte Técnico y, contra todos los pronósticos, el Galardón principal. Y ellos que solo pensaban que lograrían obtener por su proyecto que sus profesores los invitaran a cenar a algún elegante restaurante.

Tras su inesperado triunfo, los medios se fijaron en estos jóvenes. Así, por ejemplo, la prestigiosa revista de tecnología Wired publicó su historia, en la que calificó a Arcega como un “genio”. Más importante aún, han recibido 90.000 dólares en donaciones hechas por empresas y particulares de Estados Unidos, Australia y Nueva Zelanda. El dinero lo pusieron en una cuenta común, que ya está siendo usada por Óscar y Luis, que se graduaron de la secundaria. Arcega, por su parte, aún tiene dos años más para pensar en su futuro. Dice que ya ha recibido ofertas de universidades, que le gustaría ganar becas y poder ir a estudiar ingeniería al MIT. Algo que no podría lograr cualquiera, ya que en EU los cerca de 60.000 ilegales que se gradúan al año de las secundarias no pueden postularse a becas o a subsidios gubernamentales.

Diez años después, estos cuatro jóvenes lograron vencer las estadísticas, tanto que incluso serán retratados en una película. Aquí sus historias:

Lorenzo Santillan

Santillan, el “genio de la mecánica” del equipo, utilizó el dinero para graduarse de la carrera de gastronomía. Ahora él y Luis Aranda son dueños de una compañía de alimentos en Phoenix. Además de trabajar como mecánico en su tiempo libre.

Luis Aranda

Aranda era el único ciudadano legal en Estados Unidos al momento de ganar la competencia, hoy trabaja con Santillan y en como conserje en la corte de Phoenix.

Oscar Vazquez

Gracias al dinero recaudado, Vazquez se graduó de la Universidad Estatal de Phoenix, pero al no poder resolver sus problemas de migración tuvo que regresar a México. El senador Dick Durban se enteró del caso y lo ayudó a obtener amnistía y poder regresar a EU. A su regreso, Vazquez se enlistó en el ejército y participó en el combate en Afganistán. Hoy es mecánico para los ferrocarriles BNSF en Montana.

Cristian Arcega

Arcega, el ingenioso y creativo del equipo, no pudo terminar una carrera debido a la falta de recursos, hasta que se pasó una ley electoral que subsidiaba las cuotas de educación para inmigrantes indocumentados. Por un tiempo Arcega trabajó en Home Depot y ahora ayuda en el negocio de su vecino. Además de eso, “paso la mayoría de mi tiempo trabajando en ideas para productos nuevos”.

Fuente: El Tiempo

Fotos: WIRED

http://www.educacionyculturaaz.com/ciencia-y-tecnologia/inmigrantes-mexicanos-le-ganaron-al-instituto-de-tecnologia-de-massachussets-mit

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)

Archivo del blog

-

►

2025

(1457)

- ► septiembre (155)

-

►

2024

(1083)

- ► septiembre (107)

-

►

2023

(855)

- ► septiembre (72)

-

►

2022

(630)

- ► septiembre (27)

-

►

2021

(1053)

- ► septiembre (59)

-

►

2020

(1232)

- ► septiembre (75)

-

▼

2017

(271)

- ► septiembre (27)

-

▼

enero

(43)

- Bill Hicks

- Eric Lomax

- Existencia

- Inside

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez

- Fernando Savater

- Mijail Bakunin

- PIERRE JOSEPH PROUDHON

- Simone Weil

- Manuela León

- Battle of Cable Street

- George Carlin - strange culture

- Bill Hicks

- Countess Markievicz

- Harry Gregg

- Simone de Beauvoir

- Orígen Capitalista

- Los inmigrantes mexicanos que le ganaron al MIT

- Louis Zamperini

- George Orwell

- Marino Morikawa

- Peter Kennard

- Paul J Meyer

- George Carlin - You are a slave

- Walt Whitman

- Chris Rock. Bring The Pain

- Eve Ensler

- Gabriel Salazar

- Jose Luis Sampedro

- Alice Walker

- Angela Davis

- Dolores Cacuango

- Bill Hicks

- Alejandro Jodorowsky

- George Carlin

- How Laughter Makes Life Better

- Louis Zamperini

- Mónica Lavin

- Vivir

- Carl Sagan

- Eduardo Galeano

- Society Trap - Joe Rogan

- Rinku Singh y Dinesh Patel

-

►

2016

(153)

- ► septiembre (29)

-

►

2015

(385)

- ► septiembre (4)

-

►

2014

(561)

- ► septiembre (15)

-

►

2013

(1053)

- ► septiembre (68)

-

►

2012

(717)

- ► septiembre (108)