"De una cosa estoy seguro: mis siete libros de Las crónicas de Narnia y los tres de ciencia-ficción comenzaron cuando se me pasaban por la cabeza ciertas imágenes. Al principio, no había historia, sólo imágenes. El león empezó con la imagen de un fauno que llevaba un paraguas y unos paquetes por un bosque nevado. Llevaba grabada esa imagen desde que tenía unos 16 años. Luego, cierto día, cuando rondaba los 40, me dije: 'Intentemos construir una historia a partir de esa imagen". En otros de esos ensayos, C. S. Lewis asegura que "a veces los cuentos de hadas dicen mejor lo que hay que decir", y muestra su entusiasmo por El Señor de los Anillos, de Tolkien. "Este libro es como un relámpago en un cielo despejado", escribe, y asegura que tras su lectura "ya no somos los mismos".

https://elpais.com/diario/2006/01/11/cultura/1136934006_850215.html

domingo, 23 de diciembre de 2018

G.K. Chesterton

Nació el 29 de mayo de 1874 en Londres, Inglaterra. De niño aprendió de memoria las mejores páginas de literatura inglesa y le gustaba recitar y contar cuentos en momentos inesperados.

Escribió más de 90 libros, cientos de poemas, unos 200 cuentos e innumerables artículos, ensayos y obras menores.

“Chesterton escribe de una manera genial, profunda y luminosa, con un sentido del humor notable. Es capaz de condensar ideas profundas y explicarlas de manera sencilla”, expresó Larios.

Uno de los primeros escritos conocidos de Chesterton es una poesía a San Francisco. “Esa afinidad con el santo lo acompaña toda su vida. Fue una persona profundamente espiritual”

Flannery O'Connor

En 1958, después de que Flannery O’Connor se sumergiese en el manantial con propiedades curativas del santuario de Lourdes, dijo (parafraseando a una amiga y con la sorna que la caracterizaba) que “el verdadero milagro era no contagiarse de una epidemia a través de esa agua repugnante”. Aunque a regañadientes, había acudido allí como parte de un grupo (“mujeres católicas llevadas en manada de un lugar a otro”, como explicó ella misma) de peregrinación al centenario de Lourdes, viaje promovido por la diócesis de Savannah. La escritora, aquejada de lupus, era consciente de que no le quedaban muchos años de vida, y en ese viaje por Europa quiso intentarlo todo; entre otras cosas, una audiencia general con el papa Pío XII en la basílica de San Pedro.

Moriría seis años después, pero en todo caso la anécdota ilustra a la perfección dos importantes claves de su escritura: la ironía y su dimensión religiosa. El primer aspecto es algo que salta a la vista en una primera lectura de su obra. El segundo, sin embargo, no se percibe tan fácilmente. De hecho, cualquiera que se acerque a sus dos novelas o a sus relatos sin conocer su biografía (nacida en el sur de EE UU y descendiente de irlandeses, era católica hasta el tuétano, de misa diaria) pensaría que está ante la nihilista más desesperanzada, y que si hay alguna presencia sobrenatural en su obra es, a juzgar por el grado de salvajismo, violencia y humor negro, únicamente la del diablo.

https://elpais.com/cultura/2018/10/11/babelia/1539256825_702159.html

Carson McCullers

Bukowski retrató su final en un poema: «Murió alcohólica/envuelta en una manta/ sobre una silla plegable/ en un transatlántico./ Y todos esos libros suyos/ de aterradora soledad/ esos libros/ sobre la crueldad/ del amor sin amor/ es todo lo que de ella queda/ uno que pasaba/ descubrió su cuerpo/ y avisó al capitán/ y su cadáver fue trasladado/ a otra zona del barco/ mientras todo lo demás seguía/ exactamente como ella lo había descrito».

En la revista humorística Modern Drunkard se detallaba la dieta Carson McCullers: se saluda el día con una cerveza antes de ponerse ante la máquina de escribir, luego sorbitos de jerez mientras se escribe si es un día caluroso, si no, si hace falta leña para el horno, lingotazos de whisky. Al café le va bien un poco de brandy, y ya puestos puede que sobre el café. Antes de cenar, para celebrar el final de la jornada y las dos o tres páginas que han gateado hacia la realidad en una primera versión a la que le harán falta muchas correcciones, un martini. Luego hay que salir de fiesta o a cenar con amigos, y entonces más martinis, coñacs y whiskis. Para despedir el día, una cerveza. La dieta Carson McCullers tiene tres ingredientes: ginebra, cigarrillos y desesperación. Según Truman Capote, lo extraño no es que muriera a los 50 años, lo verdaderamente extraño es que no hubiera muerto mucho antes. Y Gore Vidal, siempre al quite, la despidió con el sintagma «la desgraciada más talentosa que he conocido».

https://www.elmundo.es/cultura/2017/01/14/5879278b268e3e0d248b463a.html

Jim Harrison

To remember you’re alive visit the cemetery of your father at noon after you’ve made love and are still wrapped in a mammalian odor that you are forced to cherish. Under each stone is someone’s inevitable surprise, the unexpected death of their biology that struggled hard, as it must. Now to home without looking back, enough is enough. En route buy the best wine you can afford and a dozen stiff brooms. Have a few swallows then throw the furniture out the window and begin sweeping. Sweep until the walls are bare of paint and at your feet sweep until the floor disappears. Finish the wine in this field of air, return to the cemetery in evening and wind through the stones a slow dance of your name visible only to birds.

Juan Ramón Jiménez

Siempre tienes la rama preparada

para la rosa justa; andas alerta

siempre, el oído cálido en la puerta

de tu cuerpo, a la flecha inesperada.

Una onda no pasa de la nada,

que no se lleve de tu sombra abierta

la luz mejor. De noche, estás despierta

en tu estrella, a la vida desvelada.

Signo indeleble pones en las cosas.

luego, tornada gloria de las cumbres,

revivirás en todo lo que sellas.

Tu rosa será norma de las rosas;

tu oír, de la armonía; de las lumbres

tu pensar; tu velar, de las estrellas.

Juan Ramón Jiménez

… Y yo me iré. Y se quedarán los pájaros cantando:

y se quedará mi huerto, con su verde árbol,

y con su pozo blanco.

Todas las tardes, el cielo será azul y plácido;

y tocarán, como esta tarde están tocando,

las campanas del campanario.

Se morirán aquellos que me amaron;

y el pueblo se hará nuevo cada año;

y en el rincón aquel de mi huerto florido y encalado,

mi espíritu errará, nostálgico…

Y yo me iré; y estaré solo, sin hogar, sin árbol

verde, sin pozo blanco,

sin cielo azul y plácido…

Y se quedarán los pájaros cantando.

Juan Ramón Jiménez

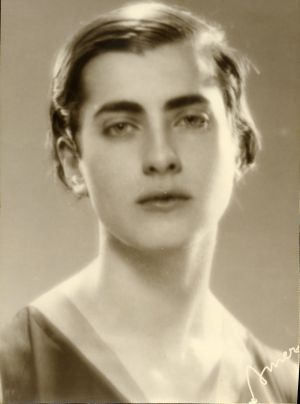

Ya no puedo vivir sin ti, Juan Ramón

El conmovedor diario de la escultora Marga Gil, que se enamoró en secreto del poeta y Nobel español, se publica 83 años después de quitarse la vida

“No lo leas ahora”. Fueron las últimas palabras que Marga Gil Roësset dijo a Juan Ramón Jiménez, en la casa del poeta en la calle Padilla, de Madrid, mientras dejaba sobre su escritorio una carpeta amarilla. Guardaba la revelación de su amor imposible por él, que la había llevado a una decisión fatal. Marga salió del despacho del escritor, fue a su taller, en el que había trabajado en los últimos meses, y destruyó todas sus esculturas, excepto un busto de Zenobia Camprubí, la esposa de su amado. “No lo leas ahora”… Abandonó el lugar para cumplir el destino que había previsto. Pasó primero por el Parque del Retiro; luego tomó un taxi hasta la casa de unos tíos en Las Rozas y allí se disparó un tiro en la sien.

Era el jueves 28 de julio de 1932. Ella tenía 24 años; él, 51. Ocho meses antes había conocido al poeta y a su esposa, con quienes entabló una sincera y afectuosa amistad. Pero en la joven pintora y escultora, a quien Juan Ramón y Zenobia llamaban “la niña”, también se desató en silencio una pasión amorosa no correspondida. Amenazadora. Hasta que ese amor colonizó toda su vida y la convirtió en tragedia.

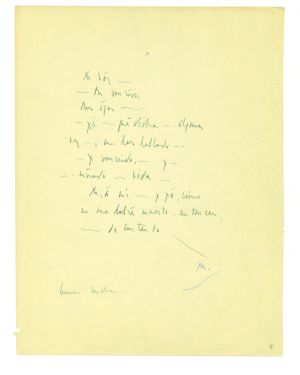

“…Y es que…

Ya no puedo vivir sin ti

…no… ya no puedo vivir sin ti…

…tú, como sí puedes vivir sin mí

…debes vivir sin mí…”.

Ese deseo lo plasmó con su letra angulosa en una de las hojas de la carpeta que entregó a Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881-1958). Las escribió en las últimas semanas de ese verano. El autor le hizo caso. “No lo leas ahora”. Un poco de sombra cubrió su corazón para siempre. Un poco de luz salió de allí para su obra poética. Ese otoño del 32, él quiso rendirle homenaje publicando el manuscrito del diario de Gil, pero no pudo. En 1936, salió casi inesperadamente al exilio por la Guerra Civil. Ochenta y tres años después del suicidio de Marga Gil y de la voluntad de Juan Ramón Jiménez (JRJ), ese deseo del poeta se convierte ahora en realidad. Se titula Marga. Edición de Juan Ramón Jiménez y está editado por la Fundación José Manuel Lara. Suma un prólogo de Carmen Hernández-Pinzón, representante de los herederos de JRJ; un texto de Marga Clarck, sobrina de la artista, y escritos del poeta y su mujer sobre Marga Gil. Un relicario literario acompañado por facsímiles de las anotaciones de la esculhttps://elpais.com/cultura/2015/01/27/actualidad/1422383194_216666.htmltora y varios de sus dibujos y fotos.

Amor, silencio, alegría, desesperación, amor. El desconcierto se plasma en la nota que la joven dejó a Zenobia Camprubí: “Zenobita… vas a perdonarme… ¡Me he enamorado de Juan Ramón! Y aunque querer… y enamorarse es algo que te ocurre porque sí, sin tener tú la culpa… a mí al menos, pues así me ha pasado… lo he sentido cuando ya era… natural… que si te dedicaras a ir únicamente con personas que no te atraen… quitarías todo peligro… pero eso es estúpido”.

Esa confesión figuraba en aquel diario extraviado tantísimos años. Desde 1939, cuando tres asaltantes —Félix Ros, Carlos Martínez Barbeito y Carlos Sentís— robaron la casa de JRJ mientras se hallaba en el exilio. El poeta, quien ganaría el Nobel de Literatura en 1956, siempre estuvo inquieto por el destino de esos documentos. Siempre preguntaba por ellos a su gran amigo Juan Guerrero. Lo recuerda Carmen Hernández-Pinzón, hija de Francisco, sobrino del autor de Espacio y representante de sus herederos. Parte de ellos fueron divulgados en 1997 por el diario Abc. El suicidio de Gil afectó mucho a JRJ y a su esposa. “Los dos quedaron muy abatidos, y él no quiso escribir durante un tiempo. Nunca la olvidaron”, dice Carmen.

Ese “No lo leas ahora” es un asomo al amor que revitaliza la vida y, a su vez, esteriliza a quien no es correspondido, mientras vive de migajas secretas que son el triunfo de su existencia:

“…Y no me ves… ni sabes que voy yo… pero yo voy… mi mano… en mi otra mano… y tan contenta…

…porque voy a tu lado”.

Ahora todos lo saben. Y ella fue más que ese feliz y fatal susurro amoroso. “Quiero que se la conozca como la genial artista que fue y sigue siendo. Muchas estudiosas y especialistas en las vanguardias del siglo XX han dedicado su tiempo a investigar su obra”, cuenta Marga Clarck. La publicación del diario le parece importante, ahora que la figura de su tía se empieza a reconocer. Confía en que sirva “para que ella pueda navegar sola porque su obra es muy potente. Y Juan Ramón quería que ella pasara a la historia como artista”.

El poeta lo sabía. Ese amor desconocido era parte feliz de su vida, aunque no lo pidiera. Era suyo, también. Un rincón de su casa lo inmortalizó. Tras la muerte de Marga, mandó hacer un aparador de roble sobre el que puso el busto de Zenobia esculpido por “la niña”. La cara del amor de su vida cincelada por la mujer que no soportó vivir sin él.

https://elpais.com/cultura/2015/01/27/actualidad/1422383194_216666.html

miércoles, 5 de diciembre de 2018

Jim Harrison

Llanto por Jim Harrison

El escritor, amigo del autor de 'Leyendas de pasión', destaca el carácter claro y aventurero del fallecido

Le conocí en San Francisco. A lo largo de una cena regada por una cantidad alarmante de vino de Borgoña, el seguía lúcido, y me dio el visto bueno para dirigir un documental sobre él y su amigo el poeta Gary Snyder. Un año después, cuando se estrenó la película en el Festival Lumière, en Lyon, me confesó que aquella noche en California decidió trabajar conmigo por una razón. Me había preguntado qué era lo que más me gustaba del poeta Federico García Lorca, y le había respondido que la dureza, la mezcla de una sensibilidad única combinada con una actitud realista y implacable con respecto a la vida. Le di la definición escueta del duende lorquiano: "Es, en suma, el espíritu de la tierra".

Ese era el espíritu que Jim Harrison llevaba dentro. Dijo una vez, "he aprendido que no puedo estar bien en mi propia piel, mi auténtica casa, cuando estoy distraído pensando en otro lugar. Tienes que encontrarte donde estás, donde estás ya, en el mundo que te rodea". Su lugares favoritos en este mundo eran, Michigan, Montana, Nueva México, Francia y España. Le encantaba la poesía de Antonio Machado, y había hecho peregrinajes a Colliure para visitar su tumba. Hace solo 10 días hablaba con ilusión del viaje que tenía pendiente esta primavera a París y a Sevilla.

La muerte de Linda, su mujer, el año pasado le hundió, pero seguía escribiendo. Decía que tenía que escribir para mantener su apego a la realidad. Quería con lealtad y pasión: a sus hijos, a sus perros, a sus amigos. Iba de duro, era resistente a todo, pero tras esa actitud autoprotectora había una sensibilidad profunda. Estaba orgulloso de haber podido mantener a su familia a base de su talento literario. Despreciaba a los escritores que buscaban cobijo dando clases de creative writing en las universidades.

Harrison nació en Michigan en una familia de raíces escandinavas mezcladas con nativos americanos. Su conexión con los indígenas de Estados Unidos fue constante, y está reflejada en muchos de sus libros. El respeto que les tenía, desprovisto de toda sentimentalidad, era inmenso. Por otra parte, aunque sea más conocido como novelista, la faceta de su obra que más valoraba era la poesía. Como artista, la poesía es lo que más le preocupaba. Vivía de la prosa, pero su corazón estaba íntimamente ligado a la poesía.

Tardará mucho tiempo en nacer, si es que nace, un americano tan claro, tan aventurero. Era un tipo brusco, con su pitillo y su copa de vino, sus perros y rifles, su atuendo de cazador. Le gustaba cocinar y contar anécdotas divertidísimas, y perderse por el campo citando a Shakespeare y Machado como la cosa más natural del mundo, sin pretensión ninguna. La última vez que le vi fue hace un par de años, aquí, en Madrid. Le encantaba la ciudad. Cuando nos despedimos delante de su hotel, en frente del Museo del Prado, con ese olor a acacia flotando en el aire, me hizo prometer que leería la obras completas de René Char. No lo he hecho todavía, pero mañana empiezo.

John J. Healey es escritor. Su última novela, ‘El samurái de Sevilla’, se publica en España el 5 de abril.

https://elpais.com/cultura/2016/03/27/actualidad/1459105692_976379.html

Edward L. Bernays

“Universal literacy was supposed to educate the common man to control his environment. Once he could read and write he would have a mind fit to rule. So ran the democratic doctrine. But instead of a mind, universal literacy has given him rubber stamps, rubber stamps inked with advertising slogans, with editorials, with published scientific data, with the trivialities of the tabloids and the platitudes of history, but quite innocent of original thought. Each man's rubber stamps are the duplicates of millions of others, so that when those millions are exposed to the same stimuli, all receive identical imprints. It may seem an exaggeration to say that the American public gets most of its ideas in this wholesale fashion. The mechanism by which ideas are disseminated on a large scale is propaganda, in the broad sense of an organized effort to spread a particular belief or doctrine.”

― Edward L. Bernays, Propaganda

martes, 4 de diciembre de 2018

Jim Harrison

La lectura juvenil puede ser un procedimiento melancólico. Tu ingenuidad te hace creer todo lo que lees. Luego ese sentimiento se vuelve humorístico. "El niño lisiado pintó en su bota de vaquero. Por desgracia, dentro había una pequeña serpiente de cascabel que le mordió y lo mató lentamente. Su perro intentó revivirlo y la serpiente mordió fatalmente al perro en la nariz. Ahora hay dos amigos tocados por la muerte en el porche". Ese tipo de cosas. Sin embargo mi niñez lectora fue placentera a pesar de que perdí mi ojo izquierdo a los 7 años cuando una niña me arrojó un vaso a la cara. Esto conllevó un esfuerzo mayor en la búsqueda de alternativas reales en los libros. A los 21 años mis personas favoritas, mi padre y mi hermana, murieron en un accidente de coche y esto sirvió de combustible para escribir totalmente sin compromiso. Si la gente a la que quieres puede morir en un accidente te niegas a dar un paso atrás en tu trabajo.

http://www.elcultural.com/noticias/letras/Jim-Harrison-La-muerte-de-mi-hermana-y-mi-padre-me-sirvio-para-escribir-sin-compromiso/9121

lunes, 3 de diciembre de 2018

Joan Baez

By Mick Brown

On a warm weekend in Newport, Rhode Island, Joan Baez is sitting in the garden restaurant of the Hotel Viking, doing her best not to surrender to sentimentality or nostalgia. The next day she will be appearing on stage at the Newport Folk Festival 50, celebrating the festival’s 50th anniversary, and, more poignantly, her first appearance there – by extension the birth of her career as a professional singer. An emotional moment, then? Baez gives it a moment’s thought. 'Not really…’

Baez was a complete unknown playing in the coffee houses of Boston when she

was invited by the folk singer Bob Gibson to join him on stage at Newport.

'I walked on stage and it looked like the largest gathering of people on

earth,’ she now says with a laugh. 'I felt as if I’d been invited to my own

execution.’ Within a year, she would be the most popular folk singer in

America.

The Festival 50 performance will bring together a number of luminaries of the

1960s folk movement of which Baez would become the undisputed queen – her

old friends Judy Collins, Arlo Guthrie and the great patriarch of American

folk music, Pete Seeger. (It was Seeger, now 90, whose appearance in 1954 at

a fund-raising concert for the Democratic Party at Palo Alto High School in

California first inspired the belief in the 13-year-old Baez that she, too,

could make a life from singing.)

The Hotel Viking is one of the grandest in a town of grand establishments. It

was where Baez stayed when she first appeared at Newport, and again in 1963,

when she returned with Bob Dylan – the queen and her crown prince, prowling

around the hotel pool cracking a 20ft black leather bullwhip which a friend

of Baez’s had given Dylan as a joke. 'Ah, yes, the bullwhip. We were pretty

good with that.’

Baez gives a slight smile. Dylan, whom she famously loved, Woodstock, where

she performed, the 1960s, which she helped to define – all of this is in the

past, where Joan Baez does her best not to dwell. 'I think I’m trying to

strangle people into coming up to the present so much of the time, because

people tend to live aeons ago,’ she says.

A figure of dignified, simple elegance, she is dressed in black trousers, a

brown silk sweater and an ornate turquoise necklace. Her steel-grey hair is

neatly cropped. She has huge brown liquid eyes that seem to hint at some

perpetual, unseen amusement. For many years Joan Baez was in psychotherapy,

and has recently become an avid meditator – 20 minutes a day every day – and

her rosary of sandalwood beads is around one wrist (on the other is a silver

bracelet stamped with Nelson Mandela’s prison number, a memento of her

appearance at his 90th birthday celebrations last year). The practice lends

her a tangible calm and serenity, as if she is hovering a few inches above

the irritations and preoccupations of daily life.

'Pretty damn serene,’ she agrees.

At the age of 68 Joan Baez is enjoying something of a second summer in her career. There was a time in the early 1990s, she says, when she believed it was all but over. While she retained a loyal following in Europe, in America her record sales had plummeted to the point where she could not even find a record label. 'Everybody said, “Oh she’s great, a legend,” but they did not want to sign me. If we’d sent out demos of what I was doing and put “Young woman songwriter” on it, we’d have had a better chance than putting “Joan Baez” on it.’

With the advice of her present manager, Mark Spector, she began to rebuild her career, connecting with a younger generation of songwriters such as Natalie Merchant, Ryan Adams and Mary Chapin Carpenter. An album last year, Day After Tomorrow, produced by Steve Earle and featuring songs by Earle, Tom Waits and Thea Gilmore, became her best-selling record since the 1970s and won her a Grammy nomination.

Baez recently finished filming a documentary about her life, in the 'American Masters’ series for the American Public Broadcasting Service – which amounts to being enshrined as a great national institution. The film includes a clip of a press conference conducted in the mid-1960s, in which she is introduced as 'the folk-music star, Joan Baez’. With the mixture of haunting virginal beauty and deadly earnestness that defined her, she retorts that she doesn’t think of herself as a star: 'If people have to put labels on me, I’d prefer the first label to be human being, the second label to be pacifist, and the third to be folk singer.’

Baez’s pacifist convictions were instilled in her from an early age. Her parents, Albert and 'Big Joan’, as she was known, were Quakers – Albert a physicist who turned down the opportunity to work on lucrative defence programmes to pursue a career as a lecturer. Joan was the middle of three sisters. They were an intensely close and happy family in which independence of thought and non-conformity were encouraged.

When Joan was 10 Albert was sent by Unesco to work in Baghdad. It was her first awareness of real poverty, she remembers, and the first step in what she describes as her journey towards a sense of social justice. Reading Anne Frank’s diary at the same age was the second. 'I identified with it so strongly, her feeling that people are basically good at heart.’ The third was as a 16-year-old, hearing the young Martin Luther King speak about civil rights at a seminar run by the American Friends Service Committee in Palo Alto, where the Baezes were then living. 'I’d heard these discussions in my family for years, but he was actually doing what I had heard and read about,’ she says. (Only a few years later she would find herself marching beside King in Grenada, Mississippi, to integrate local schools, and performing on the platform at the March on Washington in August 1963, when King made his legendary 'I have a dream’ speech.)

Baez went to Boston University in 1958, although she would pursue her studies for only a few weeks. It was there that she began to perform in the burgeoning coffee-house and folk-club scene around Harvard Square. One contemporary quoted in David Hajdu’s biography of Baez, Positively 4th Street, noted that 'she gave off a kind of vulnerability, which made her singing appear like kind of a brave act. Like a beautiful bird that is terrified and doesn’t quite know why.’ The terror was real, Baez says. Performing filled her with dread, and she was sometimes so racked with nerves that she would have to leave the stage in mid-song, to splash herself with cold water and compose herself.

Baez’s emergence coincided with, and to a large extent propelled, the folk-music boom of the early 1960s. Her first two albums were of traditional songs, melancholic ballads about love and murder, which, Baez recalls, she 'had the sadness in me to sing’. Both went gold – unheard of for folk music. Time magazine put her on its cover; from every corner she was beatified as 'the Madonna of folk’.

Baez was not interested in entertaining people so much as in moving them, making them feel. And in this she was true to the spirit of the times. It was Bob Dylan who would turn her into a protest singer. Dylan was a virtual unknown when he and Baez first met at a Greenwich Village club, Gerde’s Folk City, in 1961. Dylan initially antagonised her by trying to pick up her younger sister, Mimi. It was Mimi’s boyfriend, the songwriter and author Richard Fariña, who supposedly told Dylan that what he needed to do was 'hook up with Joan Baez… She’s your ticket, man.’

For her part, Baez was smitten by Dylan’s anthems of protest and social change. 'It was as if he was giving voice to the ideas I wanted to express, but didn’t know how,’ she would later recall. She began to include his songs in her own repertoire, and invited him to tour with her. They became lovers, and his fame blossomed under her patronage. But once people began anointing him the 'king of protest’ he quickly declared his abdication, abandoning what he called the 'finger-pointing songs’ and refusing to lend his name to any cause. The growing distance between her political convictions and his apparent lack of them would eventually become the fault-line dividing them.

In her 1989 autobiography, And a Voice to Sing With, Baez remembers once asking Dylan what was the difference between them; simple, he replied, she thought she could change things, and he knew that no one could.

So who, I ask her, does she think was right?

'I would say we both were. Certainly for him, he’s right. But he’s not in the business of changing things. He never was. And that’s where my mistake was with him. I kept pushing him, wanting him to want to do that. Exhausting for him, and futile for me. Ridiculous. Until I finally put it together in my head that he had given us this artillery in his songs, and he didn’t really need to do anything aside from that. I mean, he may resent it, but he changed the world with his music.’

Resent it?

'Well, just because he doesn’t want to think about that sort of thing. He doesn’t want the responsibility. On the other hand, I have enough intelligence to know I don’t understand him, and that’s why it’s so futile to keep talking about him.’

Her affair with Dylan finally ended in 1966 after an unhappy British tour, when he spent much of the time ignoring her. The problem was, she says, that even when it was clear that things were over between them, she 'didn’t have the brains to leave’.

While they remained somehow forever connected – she joined him on his 'Rolling Thunder’ tour 10 years later – you sense they have long since lost touch. Baez doesn’t say.

Dylan is the ghost at the banquet in any interview with Baez, the one subject interviewers can be guaranteed to raise, the subject she most loathes talking about. When I ask why she thinks people are still fascinated by the relationship, she fixes me with a look. 'Well, that must be some sort of deficit in their lives. It’s like Woodstock. People measure their lives by it – were they there; were they born yet; were they stuck on the freeway; did their parents say they couldn’t go. They’re obsessed by it. And it was a wonderful three days; the music was great. I’m glad I was there. But it wasn’t the f***ing revolution. So I don’t really know the answer. I mean, [Dylan] and I were not just two people – we were thousands of people, everybody else’s images of whatever we were, none of them true. But why it was so huge I don’t really know.’

And nor do you care?

She laughs. 'No.’

Dylan may have abandoned protest, but Baez did not. 'Someone had to change the world,’ she notes wryly in her autobiography. 'And obviously I was the one for the job.’

In 1964 she publicly refused to pay the proportion of her income tax that went to the defence budget, in protest against America’s deepening involvement in Vietnam. And the following year, with a friend and mentor, Ira Sandperl, she established the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence in her hometown of Carmel, California, to teach peace studies.

The writer Joan Didion was among the visitors, writing a celebrated essay, 'Where the Kissing Never Stops’, in which she waspishly described Baez as being 'a personality before she was entirely a person’, taking note of the various roles that the media had assigned to her: 'the Madonna of the disaffected… the pawn of the protest movement… the girl ever wounded, ever young.’

Baez says she remembers being hurt by that – not the part about her being a personality before she was a person, 'that was perfectly true. I didn’t like that she didn’t take my politics as deadly seriously as I did. Which means, of course, that she was probably right. I was pretty young.’

So does she look back on that younger self as idealistic and naive?

'Not really. If you look at stuff I said, it was usually pretty right on. You might say idealistic, or you might say it was impossible to realise in this lifetime; but it was correct.’

Too serious-minded, perhaps?

'Too self-certain. But that came from the uncertainty about myself.’

Humourless, perhaps?

'I think I kept it under wraps. Because I was hysterical when I was with my family and friends. But pretty humourless in the face of the cameras. And desperately soul-searching, talking to people like you – desperately wanting to be real, you know, and not phoney.’

Were you happy?

'I don’t think I was particularly happy. I think I was sort of dreamy.’

Did the recognition make you happy?

She thinks about this. 'I make a joke in concert now, when they’re clapping and clapping – “Oh, I was never interested in the money; it was the adulation.” But it’s the truth.’

In 1968, at the age of 27, Baez married David Harris, a leader of the movement resisting the draft for Vietnam. They had met in the Santa Rita Rehabilitation Centre in California, where she and her mother had been incarcerated for 45 days for blocking the doorways of the Armed Forces Induction Centre in Oakland. Harris, she recalled in her autobiography, 'was wearing a cowboy hat and looking six foot three, which he is. His smile was one of the sweetest in the world, and his eyes were a shade that a friend of mine calls “unfair blue”.’

Time called it 'the wedding of the century’. In July 1969 Harris was imprisoned again for refusing induction into the draft. Baez was pregnant with their son, Gabe, by then; shortly afterwards she performed at Woodstock. But within three months of Harris’s release from jail they separated, and were divorced in 1972.

In that same year Baez travelled to Hanoi for three weeks as a guest of the North Vietnamese and to deliver mail to American PoWs. On her third night in the city the Americans began what became known as the 'Christmas bombing’ of the city, which continued for 11 days. She remembers fortifying herself with a French saying, 'Je n’ai pas peur – je tremble avec courage.’ But the truth was she had never felt more scared. 'It was the first time I’d ever really felt mortal. 'All of my disguises for fear of death went poof! in the face of real death. Then as soon as I was in the airplane heading home, my fear of vomiting in the airplane comes back, and as we were circling the airport at home to land all my stuff was back, because I was allegedly safe from bombs.’

The maimed and broken bodies lying in the streets after the raids, and the frightened and confused American PoWs, were the most shocking and heartbreaking spectacle Baez says she has ever seen. For years she suppressed all of the horror she had felt. It was not until 2005, when she joined a peace march to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, that it finally came out.

'I put my hands on the wall [where the names of all the servicemen who died or went missing in Vietnam are inscribed], and I just wanted to go into it, and I just screamed my lungs out, and I couldn’t stop screaming. And that, so far, is how I’ve dealt with Hanoi.’

Baez was much criticised by the right for visiting Hanoi, and then, five years later, attacked by the left when she organised full-page advertisements in four major American newspapers criticising human-rights abuses by the new communist Vietnam government. Jane Fonda was among those who excoriated her for that. 'Not a heavy,’ she says briskly. 'She wrote me this terrible letter – it was not even spelt properly. But it was not pressure.’

I sense, I say, that she does not have much time for Fonda.

'Not for her politics. I met her a couple of months ago, and she embraced me so hard. And she was teary. And I embraced her back. I think she has so many regrets and she got hit so hard for that stupid thing she did in Vietnam [when Fonda visited Hanoi in 1972 she allowed herself to be photographed seated on an anti-aircraft gun]. I was sad for her over that. I think her heart was in the right place, but she wasn’t made to be political.’ Baez smiles. 'All the stuff they say about me…’

Baez never remarried following her divorce from David Harris. Had she known then what years of psychotherapy have taught her since, things might have been different, she says; but her marriage had been 'doomed’ from the start, not because of any failing on Harris’s part – 'it was the perfect match’ – but because, as she now puts it, she 'was completely promiscuous’.

The psychotherapy has lent Baez a perspective, and a vocabulary, to talk about this with a disarming candour: 'I was terrified of any intimacy. That’s why 5,000 people suited me just fine. But one-on-one, it was either completely transient – after the concert and be gone next day, and then my participation would make me sick – or it was something that I thought was real but just turned out to be heartbreaking.’

She was close to Steve Jobs, the founder of Apple ('briefly’); and to Mickey Hart of the Grateful Dead. But she is at a stage now, she says, where if 'something walked into my life that made sense’ she doubts she would recognise it. 'It certainly is not something I’m going to go looking for, because it seems like an enormous amount of work to construct something I’ve never known.’

This is not necessarily a sad thing, she says, 'if I’m happy, which I am. And if it didn’t – whatever it is – come my way, then maybe someday I’d be terribly lonely, or maybe I won’t be terribly lonely, because I will have constructed my life in a way that it makes sense.’

Her son, Gabe, is now 39, married with a daughter, Jasmine; Gabe is a percussionist who plays in Baez’s band. She says she has always been haunted by the fact that in the years when he was growing up she was often away, either performing or lending her name to a myriad humanitarian causes – supporting the mothers of the 'disappeared’ in Chile and Argentina, performing for Lech Walesa in Gdansk during the Solidarity period.

'It nags me all the time – and he always says the same thing: “Mum, you were there at a time in history when you were the only one who could have done what you did, and I had experiences in my childhood that no other kid could have had.”

I say, “I know that Gabe, but I need to know that I was also a mom.” And he says, “Yes you were a mom.” So it’s my problem.’ She pauses for a moment. 'As we know, forgiveness of oneself is the hardest of all the forgivenesses.’

Baez’s sister Mimi died of cancer at the age of 56 in 2001. Mimi had a modest reputation of her own as a folk singer, but she was always under the shadow of her elder sister. When Mimi was 18 she married Richard Fariña, a mercurial and charismatic figure who was to die in a motorcycle accident two days after the publication of his first novel, Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me – on April 30, 1966. It was Mimi’s 21st birthday, and just three months before Bob Dylan was involved in the motorcycle accident that was to prove a watershed in his career.

Baez and her sister were very close, she says, and her untimely death was 'hideous. Towards the end, she gave me the gift of being so awful to me, almost to make it less hard.’ Her father, Albert, died in 2007. Both of these deaths seemed to have the effect of sharpening Baez’s awareness of mortality, made her mindful of the fact that, as she puts it, she had 'work to do’ in that regard.

She has started spending time at the Spirit Rock retreat of the distinguished American Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield, with a view to preparing herself, she says, for her mother’s passing. Big Joan is now 96 and lives with Baez in California.

'I’m watching the ageing process,’ Baez says. She laughs. 'Actually, she’s really impossible a lot of the time. She still has her sense of humour, and she still loves men. We take her to hospital, and she’ll flirt with the Indian doctor, “Ooh, you have such lovely brown hands.” They ask her, do you know who’s the President? “Abraham Lincoln”. No, it’s Barack Obama. “Oh, but they have so much in common…” She is wonderful.’

She wants to prepare herself for being with her mother when she dies, she says.

'I’m really, really attached to her and I will miss her terribly; but then I was thinking, you know what, maybe it doesn’t have to be some terrible, dark sinking hole of depression – maybe it can be in some ways a wonderful experience.’

The following afternoon, Baez walks out of the hotel, a change of clothes over her arm, her young assistant beside her toting a guitar case, and climbs into a car waiting to take her to the festival site. She is wearing black jeans, sandals and a shimmering silk bolero jacket, like a matador’s suit of lights. The 'American Masters’ documentary about her life is being previewed in Los Angeles, and Baez has arranged to do a press conference via satellite link in a yacht club near the festival site. The presenter introduces her as 'the woman who has rightly been called the conscience of her generation’.

The very first question from the floor is, 'What is your relationship with Bob Dylan these days? Baez smiles serenely. 'Well, I don’t really have one…’

Someone else asks her if she still considers herself a protest singer. 'The foundation of my beliefs is the same as it was when I was 10,’ she says. 'Non-violence.’ If there is something she can do, then she will do it, she tells me later.

When the civil uprising occurred in Iran earlier this year she recorded a version of We Shall Overcome with a verse in Farsi and posted it on YouTube as a gesture of solidarity. The response, she says, was overwhelming.

She has always been guided by optimism, 'but nowadays the state of the world doesn’t look terribly good, does it, especially with global warming hanging over our heads on top of everything else.

I look at Gabe, his wife and daughter, and think, what’s going to happen?’ She pauses. 'I’m a little concerned about offering hope. But one has to bash on regardless, as you British say.’ She laughs. 'I love that.’

Backstage it is like a gathering of old friends, as Baez embraces Pete Seeger and Judy Collins in a warm hug. The audience is some 15,000 strong, a profusion of grey beards and ponytails, younger families. The air is permeated by a warm sense of sentiment and expectation. 'Fifty years later!’ says Baez as she walks on to the stage. 'My goodness gracious. And we really are putting one foot in front of the other!’

She sings old songs – Silver Dagger, which she first sang 50 years ago – and new ones, her voice as pure as ever it was. Singing Dylan’s Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right, she falls into a teasing impression of his nasal twang during the final verse:

'I ain’t sayin’ you treated me unkind/You could have done better but I don’t mind/You just kinda wasted my precious time…’ – bringing a roar of recognition from the crowd.

At the end, all the performers crowd on to the stage for a grand finale of When the Saints, followed by a Cajun hoe-down. And as the tempo increases and the temperature rises, Joan Baez kicks off her sandals and dances and dances, as if she hasn’t a care in the world.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/worldfolkandjazz/6173753/Joan-Baez-interview.html

domingo, 2 de diciembre de 2018

Philip K Dick

Una anécdota de Philip K. Dick, narrada por él mismo, acerca de su primer relato de ciencia ficción publicado en julio de 1952, Aquí yace el wub (Beyond Lies the Wub):

"Mi primera historia publicada, en la más deleznable de las revistas baratas que se vendían en aquel tiempo, Planet Stories. Cuando llevé cuatro ejemplares a la tienda de discos en la que trabajaba, un cliente me miró y, con ciertos reparos, me preguntó: "Phil, ¿tú lees esta clase de basura?". Tuve que admitir que no sólo la leía, sino que también la escribía."

Edward Bernays

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country. ...We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of. This is a logical result of the way in which our democratic society is organized. Vast numbers of human beings must cooperate in this manner if they are to live together as a smoothly functioning society. ...In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons...who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.”

― Edward Bernays, Propaganda

― Edward Bernays, Propaganda

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)

Archivo del blog

-

►

2025

(1373)

- ► septiembre (155)

-

►

2024

(1083)

- ► septiembre (107)

-

►

2023

(855)

- ► septiembre (72)

-

►

2022

(630)

- ► septiembre (27)

-

►

2021

(1053)

- ► septiembre (59)

-

►

2020

(1232)

- ► septiembre (75)

-

►

2017

(272)

- ► septiembre (28)

-

►

2016

(153)

- ► septiembre (29)

-

►

2015

(385)

- ► septiembre (4)

-

►

2014

(561)

- ► septiembre (15)

-

►

2013

(1053)

- ► septiembre (68)

-

►

2012

(717)

- ► septiembre (108)