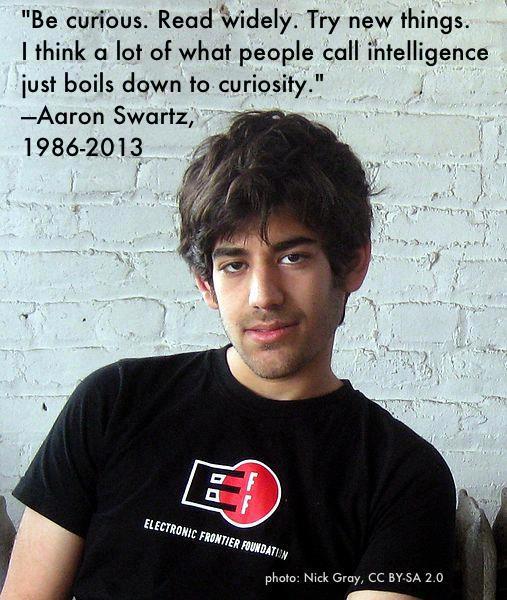

We often say, upon the passing of a friend or loved one, that the

world is a poorer place for the loss. But with the untimely death of

programmer and activist Aaron Swartz, this isn’t just a sentiment; it’s

literally true. Worthy, important causes will surface without a champion

equal to their measure. Technological problems will go unsolved, or be

solved a little less brilliantly than they might have been. And that’s

just what we know. The world is robbed of a half-century of all the

things we can’t even imagine Aaron would have accomplished with the

remainder of his life.

Aaron Swartz committed suicide Friday in New York. He was 26 years old.When he was 14 years old, Aaron helped develop the RSS standard; he went on to found Infogami, which became part of Reddit. But more than anything Aaron was a coder with a conscience: a tireless and talented hacker who poured his energy into issues like network neutrality, copyright reform and information freedom. Among countless causes, he worked with Larry Lessig at the launch of the Creative Commons, architected the Internet Archive’s free public catalog of books, OpenLibrary.org, and in 2010 founded Demand Progress, a non-profit group that helped drive successful grassroots opposition to SOPA last year.

“Aaron was steadfast in his dedication to building a better and open world,” writes Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle. “He is among the best spirits of the Internet generation. I am crushed by his loss, but will continue to be enlightened by his work and dedication.”

In 2006 Aaron was part of a small team that sold Reddit to Condé Nast , Wired’s parent company. For a few months he worked in our office here in San Francisco. I knew Aaron then and since, and I liked him a lot — honestly, I loved him. He was funny, smart, sweet and selfless. In the vanishingly small community of socially and politically active coders, Aaron stood out not just for his talent and passion, but for floating above infighting and reputational cannibalism. His death is a tragedy.

I don’t know why he killed himself, but Aaron has written openly about suffering from depression. It couldn’t have helped that he faced a looming federal criminal trial in Boston on hacking and fraud charges, over a headstrong stunt in which he arranged to download millions of academic articles from the JSTOR subscription database for free from September 2010 to January 2011, with plans to release them to the public.

JSTOR provides searchable, digitized copies of academic journals online. MIT had a subscription to the database, so Aaron brought a laptop onto MIT’s campus, plugged it into the student network and ran a script called keepgrabbing.py that aggressively — and at times disruptively — downloaded one article after another. When MIT tried to block the downloads, a cat-and-mouse game ensued, culminating in Swartz entering a networking closet on the campus, secretly wiring up an Acer laptop to the network, and leaving it there hidden under a box. A member of MIT’s tech staff discovered it, and Aaron was arrested by campus police when he returned to pick up the machine.

The JSTOR hack was not Aaron’s first experiment in liberating costly public documents. In 2008, the federal court system briefly allowed free access to its court records system, Pacer, which normally charged the public eight cents per page. The free access was only available from computers at 17 libraries across the country, so Aaron went to one of them and installed a small PERL script he had written that cycled sequentially through case numbers, requesting a new document from Pacer every three seconds, and uploading it to the cloud. Aaron pulled nearly 20 million pages of public court documents, which are now available for free on the Internet Archive.

The FBI investigated that hack, but in the end no charges were filed. Aaron wasn’t so lucky with the JSTOR matter. The case was picked up by Assistant U.S. Attorney Steve Heymann in Boston, the cybercrime prosecutor who won a record 20-year prison stretch for TJX hacker Albert Gonzalez. Heymann indicted Aaron on 13 counts of wire fraud, computer intrusion and reckless damage. The case has been wending through pre-trial motions for 18 months, and was set for jury trial on April 1.

Larry Lessig, who worked closely with Aaron for years, disapproves of Aaron’s JSTOR hack. But in the painful aftermath of Aaron’s suicide, Lessig faults the government for pursuing Aaron with such vigor. “[Aaron] is gone today, driven to the edge by what a decent society would only call bullying,” Lessig writes. “I get wrong. But I also get proportionality. And if you don’t get both, you don’t deserve to have the power of the United States government behind you.”

Update: Aaron’s parents, Robert and Susan Swartz, his two brothers and his partner, Taren Stinebrickner-Kauffman, have established a memorial website for him, and released this statement.

Our beloved brother, son, friend, and partner Aaron Swartz hanged himself on Friday in his Brooklyn apartment. We are in shock, and have not yet come to terms with his passing.

Aaron’s insatiable curiosity, creativity, and brilliance; his reflexive empathy and capacity for selfless, boundless love; his refusal to accept injustice as inevitable—these gifts made the world, and our lives, far brighter. We’re grateful for our time with him, to those who loved him and stood with him, and to all of those who continue his work for a better world.

Aaron’s commitment to social justice was profound, and defined his life. He was instrumental to the defeat of an Internet censorship bill; he fought for a more democratic, open, and accountable political system; and he helped to create, build, and preserve a dizzying range of scholarly projects that extended the scope and accessibility of human knowledge. He used his prodigious skills as a programmer and technologist not to enrich himself but to make the Internet and the world a fairer, better place. His deeply humane writing touched minds and hearts across generations and continents. He earned the friendship of thousands and the respect and support of millions more.

Aaron’s death is not simply a personal tragedy. It is the product of a criminal justice system rife with intimidation and prosecutorial overreach. Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney’s office and at MIT contributed to his death. The US Attorney’s office pursued an exceptionally harsh array of charges, carrying potentially over 30 years in prison, to punish an alleged crime that had no victims. Meanwhile, unlike JSTOR, MIT refused to stand up for Aaron and its own community’s most cherished principles.

Today, we grieve for the extraordinary and irreplaceable man that we have lost.

El suicidio de Aaron Swartz, símbolo de la lucha por internet

Cuando estaba en la Universidad de Harvard, Aaron Swartz usó su acceso de estudiante al sistema de JSTOR, una editorial de ensayos académicos, para bajar cuatro millones de artículos y repartirlos gratis en internet.

Al darse cuenta, Harvard le cortó su acceso a JSTOR, pero Swartz -que desde muy joven demostró su destreza en la informática- se dirigió al campus de Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT, por sus siglas en inglés), otra prestigiosa universidad en Boston, EE.UU., y se coló a un cuarto de cables y equipos electrónicos donde bajó los artículos manualmente.

El 19 de julio de 2011 Swartz fue arrestado por cargos de crimen informático, violación de los términos de uso de JSTOR y entrar a un área restringida.

Swartz se declaró inocente y esperaba ir a la corte dentro de dos meses para defender su causa, que probablemente no se reducía al caso de los artículos.

La policía de Nueva York encontró este fin de semana el cuerpo muerto de Swartz en su apartamento. El estadounidense de 26 años se ahorcó.

Su suicidio ha generado todo tipo de reacciones en el gremio de la tecnología, muchas de ellas culpando a quienes lo llevaron a las cortes de la justicia.

Swartz manifestó sus tendencias depresivas varias veces en sus blogs e incluso mencionó que solía pensar en suicidarse.

Aunque el vínculo de la muerte con el robo de los artículos de JSTOR no es claro, muchos creen que lo es y han enmarcado el suceso dentro del debate sobre el libre acceso a la información en internet.

DE PRODIGIO A ACTIVISTA

Cuando tenía 13 años y vivía con sus padres en Chicago, Swartz se ganó una beca que lo llevó a pasar unos meses en el MIT y conocer a importantes personalidades del mundo de la tecnología.

Tenía 14 años cuando hizo parte del equipo que inventó el RSS, un revolucionario formato para indicar o compartir contenido en la web de manera simple y efectiva.

Después de salir de la Universidad de Stanford sin haber terminado el currículo, Swartz fundó la empresa que en 2005 se convertiría en Reddit, una red social para la promoción de contenido que hoy en día no solo es visitada por millones de personas al mes sino también es considerada un ejemplo de innovación en internet.

La editorial Condé Nast compró Reddit en 2006 por una enorme fortuna que hizo a Swartz un joven millonario. La compra lo llevó a San Francisco, donde se deprimió y renunció al poco tiempo.

En 2010 Swartz se vinculó al Centro de Ética Edmond Safra de la Universidad de Harvard. Fue uno de los promotores de la campaña que hundió a ley SOPA en el Congreso de EE.UU., la cual buscaba establecer controles más rígidos al libre flujo del contenido en internet.

¿PRODUCTO DE LA PERSECUCIÓN?

Su faceta de activista es lo que ha hecho que su muerte sea vista como un nuevo símbolo de la lucha por una internet neutral.

No en vano el inventor de la World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, tuiteó: "Aaron está muerto. Caminantes del mundo, perdimos a uno de nuestros sabios. Hackers por derecho, perdimos a uno de los nuestros. Padres todos, perdimos a un hijo. Lloremos".

Y organizaciones y personalidades de este gremio se han pronunciado en ese sentido, entre otras el portal de filtración de documentos WikiLeaks y el promotor de leyes para el flujo de contenido gratuito Creative Commons.

Aaron Swartz finalmente no publicó los artículos por los que lo arrestaron en 2011. De hecho, los devolvió. JSTOR manifestó que no quería verlo enjuiciado y MIT se mantuvo ambigua sobre su voluntad.

Pero según el experto Glenn Greenwald, que escribió sobre el tema en el diario The Guardian, "los fiscales federales ignoraron la voluntad de las supuestas víctimas (...) e insistieron en acusarlo por delitos que implican sentencias de varias décadas y más de 1 millón de dólares en multas".

Que la persecución judicial a Aaron Swartz esté vinculada a la intención de ciertos sectores de la política estadounidense de restringir la internet es una interrogante que con dificultad se puede contestar. Lo mismo ocurre con el vínculo entre esa persecución y su muerte.

Cualquiera que sea la razón que lo llevó a suicidarse, la muerte de Aaron Swartz ya es símbolo de una pelea que para muchos es de vida o muerte. Una batalla perdida en una guerra por ganar.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario