At a Quebec City celebration of the 70th anniversary of World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic last weekend, Minister of Veterans’ Affairs, Steven Blaney, responded to a question about Canadian military sacrifice with the statement: “There would be no ‘Gangnam Style’ if it had not been for the sacrifice of Canadians, and members of the United Nations who fought off Communism.”

While I enjoy Psy’s South Korean hit as much as Minister Blaney to say it was worth one of the most brutal and least understood wars of the 20th century is a bit of a stretch.

After the Communists took control of China in 1949 the US tried to encircle the country. They supported Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan, built military bases in Japan and backed a right-wing dictator in Thailand. One of Washington’s early objectives in Vietnam was to “establish a pro-Western state on China’s southern periphery.” The success of China’s nationalist revolution also spurred the 1950-53 Korean War in which eight Canadian warships and 27,000 Canadian troops participated. The war left as many as four million dead.

At the end of World War II the Soviets occupied the northern part of Korea, which borders Russia. US troops controlled the southern part of the country. A year into the occupation, a cable to Ottawa from Canadian diplomats in Washington, Ralph Collins and Herbert Norman, reported on the private perceptions of US officials: “[There is] no evidence of the three Russian trained Korean divisions which have been reported on various occasions … there seems to be a fair amount of popular support for the Russian authorities in northern Korea, and the Russian accusations against the conservative character of the United States occupation in civilian Korea had a certain amount of justification, although the situation was improving somewhat. There had been a fair amount of repression by the Military Government of left-wing groups, and liberal social legislation had been definitely resisted.”

Noam Chomsky provides a more dramatic description of the situation: “When US forces entered Korea in 1945, they dispersed the local popular government, consisting primarily of antifascists who resisted the Japanese, and inaugurated a brutal repression, using Japanese fascist police and Koreans who had collaborated with them during the Japanese occupation. About 100,000 people were murdered in South Korea prior to what we call the Korean War, including 30-40,000 killed during the suppression of a peasant revolt in one small region, Cheju Island.”

In sharp contrast to its position on Japan and Germany, Washington wanted the (Western dominated) UN to take responsibility for Korea in 1947. The Soviets objected, claiming the international organization had no jurisdiction over post- WWII settlement issues (as the US had argued for Germany and Japan). Instead, Moscow proposed that all foreign forces withdraw from Korea by January 1948. Washington demurred, convincing member states to create the United Nations Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK) to organize elections in the part of Korea occupied by the US. For its part, the Soviet bloc boycotted UNTCOK. Canada joined UNTCOK even though Prime Minister Mackenzie King noted privately “the [US] State Department was simply using the United Nations as an arm of that office to further its own policies.”

The UN sponsored election in South Korea led to the long-term division of that country and Canada’s involvement in a conflict that would cause untold suffering. On May 10, 1948 the southern part of Korea held UNTCOK sponsored elections. In the lead-up to the election leftwing parties were harassed in a campaign to “remove Communism” from the south. As a result leftwing parties refused to participate in elections “wrought with problems” that “provoked an uprising on the island of Cheju, off Korea’s southern coast, which was brutally repressed.”

After the poll Canada was among the first countries to recognize the Republic of Korea in the south, effectively legitimizing the division of the country. External Affairs minister Lester Pearson sent Syngman Rhee, who became president, a note declaring “full recognition by the Government of Canada of the Republic of Korea as an independent sovereign State with jurisdiction over that part of the Korean peninsula in which free elections were held on May 10 1948, under the observation of the United Nations Temporary Commission.” Conversely, Ottawa refused to recognize the North, which held elections after the South, and opposed its participation in UNTCOK reports. For Pearson the South held “free elections” while those in the North “had not been held in a democratic manner” since the Soviets did not allow UNTCOK to supervise them. After leaving office Pearson contradicted this position, admitting “Rhee’s government was just as dictatorial as the one in the North, just as totalitarian. Indeed, it was more so in some ways.”

The official story is that the Korean War began when the Soviet-backed North invaded the South on June 25, 1950. The US then came to the South’s aid. As is the case with most official US history the story is incomplete, if not downright false. Korea: Division, Reunification, and US foreign Policy notes: “The best explanation of what happened on June 25 is that Syngman Rhee deliberately initiated the fighting and then successfully blamed the North. The North, eagerly waiting for provocation, took advantage of the southern attack and, without incitement by the Soviet Union, launched its own strike with the objective of capturing Seoul. Then a massive U.S. intervention followed.”

Korea was Canada’s first foray into UN peacekeeping/peacemaking and it was done at Washington’s behest. US troops intervened in Korea and then Washington moved to have the UN support their action, not the other way around.

The UN resolution in support of military action in Korea referred to “a unified command under the United States.” Incredibly, United Nations forces were under US General Douglas MacArthur’s control yet he was not subject to the UN. Canadian Defence Minister Brooke Claxton later admitted “the American command sometimes found it difficult to consider the Commonwealth division and other units coming from other nations as other than American forces.”

After US forces invaded, Ottawa immediately sent three gunboats. Once it became clear US forces would not be immediately victorious, Canada sent thousands of grounds troops into an extremely violent conflict.

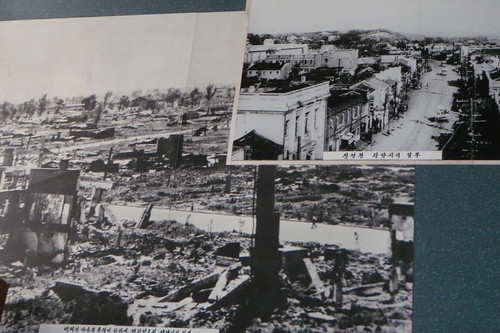

Two million North Korean civilians, 500,000 North Korean soldiers, one million Chinese soldiers, one million South Korean civilians, ten thousand South Korean soldiers and 95,000 UN soldiers (516 Canadians) died in the war. The fighting on the ground was ferocious as was the UN air campaign. US General MacArthur instructed his bombers “to destroy every means of communication and every installation, factory, city and village” in North Korea except for hydroelectric plants and the city of Rashin, which bordered China and the Soviet Union, respectively.

A New York Times reporter, George Barrett, described the scene in a North Korean village after it was captured by UN forces in February 1951:“A napalm raid hit the village three or four days ago when the Chinese were holding up the advance, and nowhere in the village have they buried the dead because there is nobody left to do so. This correspondent came across one old women, the only one who seemed to be left alive, dazedly hanging up some clothes in a blackened courtyard filled with the bodies of four members of her family. The inhabitants throughout the village and in the fields were caught and killed and kept the exact postures they had held when the napalm struck — a man about to get on his bicycle, fifty boys and girls playing in an orphanage, a housewife strangely unmarked, holding in her hand a page torn from a Sears Roebuck catalogue crayoned at Mail Order No. 3,811,294 for a $2.98 ‘bewitching bed jacket — coral.’ There must be almost two hundred dead in the tiny hamlet.”

Canadian troops denigrated the “yellow horde” of North Korean and Chinese “chinks” they fought. One Canadian colonel wrote about the importance of defensive positions to “kill at will the hordes that rush the positions.” A pro-military book notes dryly that “some [soldiers] allowed their Western prejudices to develop into open contempt for the Korean people.”

Cold War Canada summarizes the incredible violence unleashed by UN forces in Korea: “The monstrous effects on Korean civilians of the methods of warfare adopted by the United Nations — the blanket fire bombing of North Korean cities, the destruction of dams and the resulting devastation of the food supply and an unremitting aerial bombardment more intensive than anything experienced during the Second World War. At one point the Americans gave up bombing targets in the North when their intelligence reported that there were no more buildings over one story high left standing in the entire country … the overall death toll was staggering: possibly as many as four million people. About three million were civilians (one out of every ten Koreans). Even to a world that had just begun to recover from the vast devastation of the Second World War, Korea was a man-made hell with a place among the most violent excesses of the 20th century.”

But, it was all worth it, according to the Conservative government. After all South Korea has given us ‘Gangnam Style’.

Yves Engler’s latest book is The Ugly Canadian: Stephen Harper’s foreign policy. For more information visit yvesengler.com

Odio a los indiferentes. Creo que vivir quiere decir tomar partido. Quien verdaderamente vive, no puede dejar de ser ciudadano y partisano. La indiferencia y la abulia son parasitismo, son cobardía, no vida. Por eso odio a los indiferentes.

Odio a los indiferentes. Creo que vivir quiere decir tomar partido. Quien verdaderamente vive, no puede dejar de ser ciudadano y partisano. La indiferencia y la abulia son parasitismo, son cobardía, no vida. Por eso odio a los indiferentes.